Early Italian Reconstructions: Simone Martini and Nardo di Cione

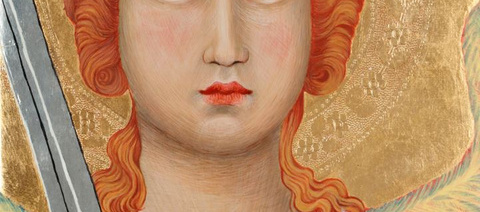

For my first-year reconstructions, I created two trecento Italian panel copies. These were Nardo di Cione’s floor brocade pattern in St John the Baptist with St John the Evangelist and St James (c. 1363-1365, 159.5 x 148cm) and Simone Martinis St Michael panel (c. 1322, 110 x 38 cm).

What was the goal the project set out to achieve?

The aim of the project was to reconstruct two fourteenth-century Italian panel paintings. These reconstructions were not done with the aim of making them perfect lasting copies, but to understand and learn about the materials, their behaviours, techniques, and the making process of such artworks. This task was navigated with the guidance of Cennino Cennini’s Craftman’s Handbook, which features a mixed set of Florentine and Sienese influences wrapped into one single source. Other sources were consulted, and progress was made through experimentation, and trial, and error.

What did I do?

Twelve radially cut boards of pine were prepared for the reconstructions with my colleague Grace An. Three layers of rabbit skin glue size were applied to provide a moisture barrier.

Gesso grosso was prepared on a glass slab and transferred to the panel, smoothing with a pallet knife. To create the gesso sottile, plaster of Paris was soaked in a bucket, stirring once a day for a month. This layer, which has a velvet-like quality, is applied with a brush.

Under-drawing was completed by tracing and carbon paper, reinforcing with ink in gum Arabic.

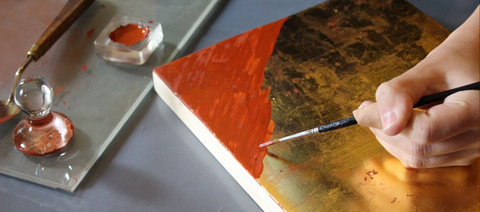

For both panels, bole was ground with water and egg whites. Fourteen layers were applied, and subsequently burnished with an agate burnisher.

The panels were water-gilded with loose gold leaf, using a 1:2 egg to water mixture to adhere it. Controlled movements and gentle handling were key. Burnishing was done with an agate burnisher.

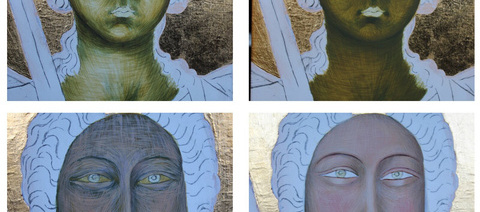

To make tempera paint, egg yolk was mixed with water to act as a binder, and ground with dry pigment. The painting method is very systematic due to the properties of tempera paint. An organised approach of paint application is required by the painter. Layers of hatched overlapping lines build up a complex network.

I soon developed a sensitivity to the colours I was observing on the original painting. Tempera painting, which was initially foreign to me, quickly became second nature.

The method of sgraffito was utilised for the di Cione panel – the opaque paint was scratched off, revealing the gilded layer beneath.

The collar and sword of St Michael received silver and tin mordant gilding. A yellow weld glaze was applied over the silver leaf. The punched motifs of the halo provide yet another effect of gold by scattering reflected light.

What was the outcome?

The number of skills learned from completing the two reconstructions (with greatly improved results in the second panel), illustrates how, by repeating such processes, one can master these skills – enabling the creation of objects that remain to be enjoyed for centuries to come.

Our reconstructions, however, are unlikely to survive this long, already exhibiting cracking, delamination, and tarnishing. It was often difficult to remember that the reconstructions were not done with the aim of making them perfect lasting copies, but to understand and learn about the materials, their behaviours, techniques, and the making process of such artworks.

What did I learn?

This project allowed me to get used to working in and navigating a studio space, dealing with supervisor’s feedback and advice, practicing my time-management skills, and improving the general sensitivity of the eye and the hand. Reading documentary sources gives insight into these processes and phenomena, but actually completing them enhances the period eye. Being able to really take my time with the work has led to me having a whole new understanding of this period’s panel painting structure and creation process, and above all a huge amount of respect for the Italian medieval artist and their surprisingly physical work.

Imperfection and mistakes usually led to greater lessons than those steps which went smoothly. In fact, this was the time to make mistakes in my career, working on a reconstruction rather than a “real” work of art. These lessons will certainly stay in mind when proceeding with other projects – and gave me a chance to practice activities such as retouching and cleaning. They allowed me to reflect carefully on what I had done, how the materials had behaved and why.

For any enquiries, or the full report, please get in touch at [email protected].

It became clear during the lengthy panel preparation and painting process just how much each previous layer affected the whole. Comparison between the original work and the reconstruction illustrated the visual impact of deterioration of the specific materials that were used and helped me to understand these mechanisms.