Modigliani up close: A conservation-led exhibition (19 September 2023)

Review by Christina Cachia

Born in 1884 Livorno, Italy, Amadeo Modigliani was one of the most influential Italian artists of the early 20th century, known internationally for his reclined nudes and elongated portraits with vacant eyes. With his art and archives being inadequately protected after his premature death in 1920, little was known of his works and technique, until Ambrogio Ceroni, a Milanese art specialist, published a catalogue on Modigliani’s works in 1970, which would be the go-to catalogue raisonné for locating original Modigliani works.

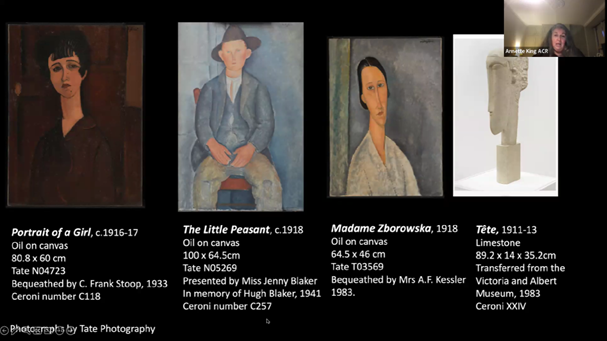

As the title suggests, Modigliani Up Close: A Conservation-led exhibition was an exhibition motivated by art historical, conservation and scientific research and findings on Modigliani’s artwork, at The Barnes Foundation from October 2022- January 2023. As Annette King, Painting Conservator at Tate and Co-Curator of the exhibition explained, the project began in 2016, whilst preparing the Modigliani exhibition at Tate Modern. Two of the three Modigliani paintings at the Tate are authenticated by the marked Ambrogio Ceroni number. The one remaining painting, without Ceroni’s authentication, sparked interest at the Tate, on whether it fitted in with other aspects that formed part of Modigliani’s technique and materials. This led to other lenders examining their Modigliani pieces, thus affording a collective direction the technical examination of Modigliani’s work. Eventually, in 2020, Annette King, Nancy Ireson (Chief curator at the Barnes), Simonetta Fraquelli (Independent art historian) and Barbara Buckley (Chief conservator at the Barnes), co-curated and conceived the Modigliani Up Close exhibition at The Barnes Foundation.

Modigliani has been the subject of many exhibitions; but as Annette highlighted, there had been no in-depth research on how the artist constructed his paintings and sculptures. The Barnes exhibition provided a limited amount of technical information throughout, so as not to detract attention from the artworks themselves. However, the exhibition offered additional information through their app ‘Barnes Foc.US’, which could reveal a more in-depth technical study of the painting in question.

Throughout this project various interesting findings were divulged regarding Modigliani’s painting technique and materials.

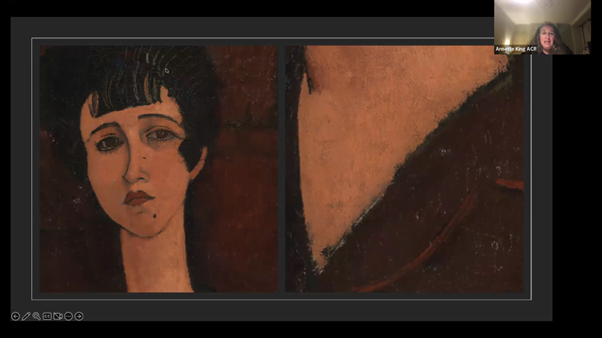

X-radiographs and observations revealed that it was a frequent practice for Modigliani to re-use his canvases, including the verso, some of which have been painted up to 6 times. In fact, he seemed to have used the underlying paintings to his advantage, allowing them to contribute to the final effect and colour of the painted subjects. In some instances, underlying paintings were also used to delineate areas, by leaving gaps between the colours. He also used the technique of scraping into the still wet paint, to reveal the colours beneath, as was seen in Painting of a Girl, 1917.

Annette goes into depth about the canvas formats that Modigliani tended to use, how these contributed to the elongated portraits and how his canvas choices were more extensive as the artist gained more commissions and relative success. Another interesting find was the use of grounds, which changed over the span of his career. Modigliani was also seen to make economic use of paints during his time in the south of France, sometimes having combined oil with tempera. And it was discovered through scientific analysis that he had used around 25 different pigments, rather than 5, as originally and historically believed.

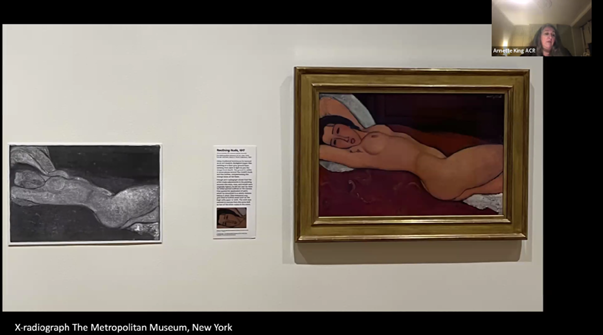

Reclining Nude (1917). This painting illustrated Modigliani’s use of a paper towel to smoothen certain areas, such as the face. Screenshot of presentation.

A particularly exciting research discovery came from the ‘automated thread count’ project. Together with Don H Johnson, C. Richard Johnson and Ella Hendrix, they managed to determine an algorithm, that could provide accurate thread counts of the canvas from a digital x-radiograph.

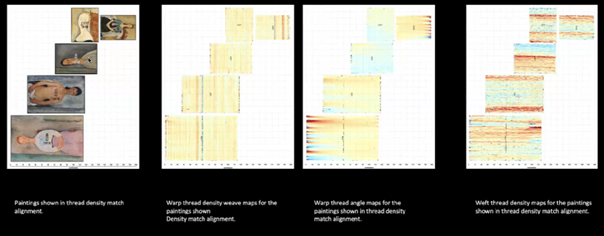

From the 79 paintings that were analysed, 36 showed to have come from 12 canvas matches. For example, match 4 (see image) shows that 5 different paintings had originated from the same piece of canvas. Léopold Zborowski, Modigliani’s art dealer, would provide him with the canvases, suggesting that Zborowski bought batches of canvases. The algorithm was also able to determine the location of the painting on this larger piece of canvas, thus displaying other areas of canvas that may have been sent to other contemporary artists, who were also taken care of by Zborowski.

Image showing ‘Match 4’ which includes the location of Modigliani’s paintings relating to the canvas piece and highlights the warp and weft thread density match alignment. Screenshot of presentation.

These and many more discoveries have been described in the Modigliani Up Close book, which was published to coincide with the exhibition that recently took place at the Barnes in 2022, and includes essays by conservators, scientists and art historians from the different institutions who had all provided vital information.

Modigliani Up Close (eds) by King, A., Fraquelli, S., Buckley, B., and Ireson, N., The Barnes Foundation (2022)

The talk by Annette King not only revealed exciting new findings into Modigliani’s practice, but also demonstrated how conservators can collaborate with other institutions, professionals, and private owners, to incorporate conservation and scientific findings throughout a public exhibition.

Christina Cachia

Christina Cachia is Assistant Paintings Conservator at Royal Museums of Greenwich, London.

She holds a Joint BA in Italian and History of Art from the University of Reading, and an MA in Conservation of Easel Paintings from Northumbria University.

Sinner to Saint: Research & Treatment of an 18th century painting from Peru (18th April 2023)

Review by Luz Vanasco

Virgen de la Candelaria (‘Virgin of the Candlelight’) is an anonymous 18th century painting from Peru. It belongs to The Phoebus Foundation, in Antwerp, which houses a varied collection, including Latin American and Spanish colonial artworks. The conservation treatment and research conducted to this oil painting on canvas (159 x 106.5 cm) was presented by paintings conservator Carlos Gonzalez Juste on 18th April 2023. He covered the context in which the painting was produced, the conservation treatment, and its technical aspects. He also discussed the iconography and symbolism of both the Virgen de la Candelaria and of an underlying painting of Mary Magdalene which had been discovered through technical examination.

Carlos addressed how, following the conquest of Mesoamerica and Mexico, the Spanish were drawn southward by South America's abundant resources. For this expansion, leaded by Francisco Pizarro, they took advantage of a civil war within the Inca Empire between Atahualpa and Huascar, which allowed the Spanish to gain control over the territory in the 1530s, which was then organised in viceroyalties. The Viceroyalty of Peru (covering from the actual Panama until Chile and Argentina) was established in 1542 with Lima as its capital. While Cuzco initially served as the capital of the Inca empire, it was deemed too distant, leading to the establishment of Lima as the new capital in 1542.

Within the Viceroyalty of Peru, there emerged a distinct artistic tradition known as the Cuzco School. While the Lima School embraced more European influences, the artists in Cuzco remained rooted in their indigenous heritage. The Cuzco School rapidly developed during the 18th century. It is characterized by the use of gold leaf in garments, known as brocateado, stereotyped facial features, hieratic frontality of the main figures, and simple distorted backgrounds. Artists often used prints as references for their work, and as the 18th century progressed, the production of artworks in workshops grew exponentially. Masters would oversee a team of assistants, enabling mass production of paintings.

Paintings from Cuzco used to be considered ‘popular’ paintings due to their planimetry, schematic forms, and their simple palette, probably by being compared with European paintings. However, in order to fully appreciate and understand these works it is important to consider that they are actual representations of sculptures present in churches. These vera effigies or painted sculptures had a sacred value and were quite popular in Cuzco, were they could be found in churches, private oratories and homes. As the popularity of these images grew, copies were made, and eventually copies of the copies, leading to the evolution and alteration of the original iconography over time.

The iconography of the Virgen de la Candelaria is based on a vision of two inhabitants from Tenerife, known as Guanche shepherds, who saw the virgin in a cliff with a candlelight, baby Jesus, and a basket of doves. It reflects the story present in the Gospel of Luke, which combines the Presentation of the Temple and the Purification of the Virgin. Moreover, the fusion of Inca beliefs in the Pachamama (mountains and hills) with Christian imagery resulted in unique representations where the triangular shape of the Virgin itself resembled mountains.

In terms of the technique, the painting is executed on a reused canvas. This was common practice in the Viceroyalty, as the production of linen and hemp was banned so there was scarcity of canvases for painting. It was painted with no ground, directly onto another composition. The background layers were applied thinly, while the figures and details were painted more thickly. This technique resulted in transparent layers and visible traces of the underlying artwork. Hands and faces were given special attention and left reserved for the master artist, while stencils were used for certain elements like the ropes. The palette is simple, and its pigments are consistent with a painting from this period and context: smalt, vermilion (probably from mines of Huancavelica in Peru), lead tin yellow, orpiment, and a copper-based pigment.

The painting had been wax lined and had a discoloured varnish, layers of grime, spots, and dirt. The uneven surface and small paint losses were related with folding marks. To address these issues, the restoration process began with surface cleaning and addressing some minor canvas deformations.

The varnish removal proved to be a delicate process due to the sensitivity of the paint. It required swelling the varnish and subsequent mechanical work, which proved to be a delicate and time-consuming process. Underneath the varnish, a layer of grime was found, requiring further cleaning with the use of buffer solutions for its removal and to diminish the dark spots. Afterwards, a first layer of dammar varnish was applied. Paint losses were then filled and textured with a Tylose and Mowiol putty commonly used at the Phoebes Foundation, which was then toned with watercolours. This was followed by another varnish layer, further retouching and a final varnish.

For the technical examination of the painting, ultraviolet fluorescence, infrared photography, infrared false colour, and X-radiography were carried out. The underlying composition depicted an angel and another figure in the centre, along with a table decorated with flowerpots and a carpet at the bottom. Further examination using macro XRF provided a clearer image of the hidden composition, revealing a fully finished representation of Mary Magdalene.

Similar representations of Mary Magdalene were found in South America, albeit with slight variations, suggesting the influence of a common source, possibly a print. However, this one in particular is quite uncommon, due to the representation of the angel and a very rich background.

The influences in the Viceroyalty of Peru extended beyond Spain. The region was also impacted by trade and cultural exchanges with Europe and Asia, particularly through the Manila-Acapulco trade route. China and Japan, in particular, played a role in providing goods to the Philippines, and then making their way to South America. These influences manifested in various ways, such as the adoption of lacas, furniture styles, and the enconchados technique in Mexico. In the underlaying painting of Mary Magdalene, the jewellery and presence of the rich comb made with ivory is a clear example of this influence as it was made in China.

Another interesting aspect is the representation of Mary Magdalene in a Spanish estrado, a small room richly decorated with Arab influences. This private space for women often had estrado or raton furnitures like the one represented with Mary Magdalene. The composition also features a tupu or ttipqui, a pin commonly used during the Inca period, highlighting the incorporation of indigenous elements.

Carlos presentation provided an insightful overview of the context and techniques of the paintings produced in 18th century Peru. These artworks transcend mere religious imagery and provide insights into the lives of the society in which they were created. The also defy simplistic comparisons with European paintings and highlight the fusion of local and external influences. The case study also shows the importance of conducting technical studies as they have proven invaluable in understanding commercial, iconographic, and societal aspects of the Viceroyalty of Peru.

Luz Vanasco

Brick by Brick – A Study of Pieter de Hooch’s Painting Technique with Anna Krekeler (12 January 2023)

Review by Jelena Zagora (Paintings Conservator, Croatian Conservation Institute)

Fostered by preparation of the retrospective exhibition Pieter de Hooch in Delft. From the Shadow of Vermeer (October 2019 – February 2020) organized by and held in Museum Prinsenhof Delft, a meticulous research on the artist's life and oeuvre was carried out. Pieter de Hooch (1629 – in or after 1679) was a Dutch painter, contemporary of Johannes Vermeer. Although much less famed, de Hooch is held in high regard for his intimate domestic scenes and skillful depictions of architecture. Little is known of the painter's biography due to scarce archival evidence; reasons for this and a sketch of his life are presented in the exhibition catalogue. Interesting concept of the exhibition setup is hinted at by the chapter titles, delineating the profile of the painter active in Rotterdam, Delft and Amsterdam, the context and development of his work and both his personal topography and the topography of the city of Delft in his paintings.

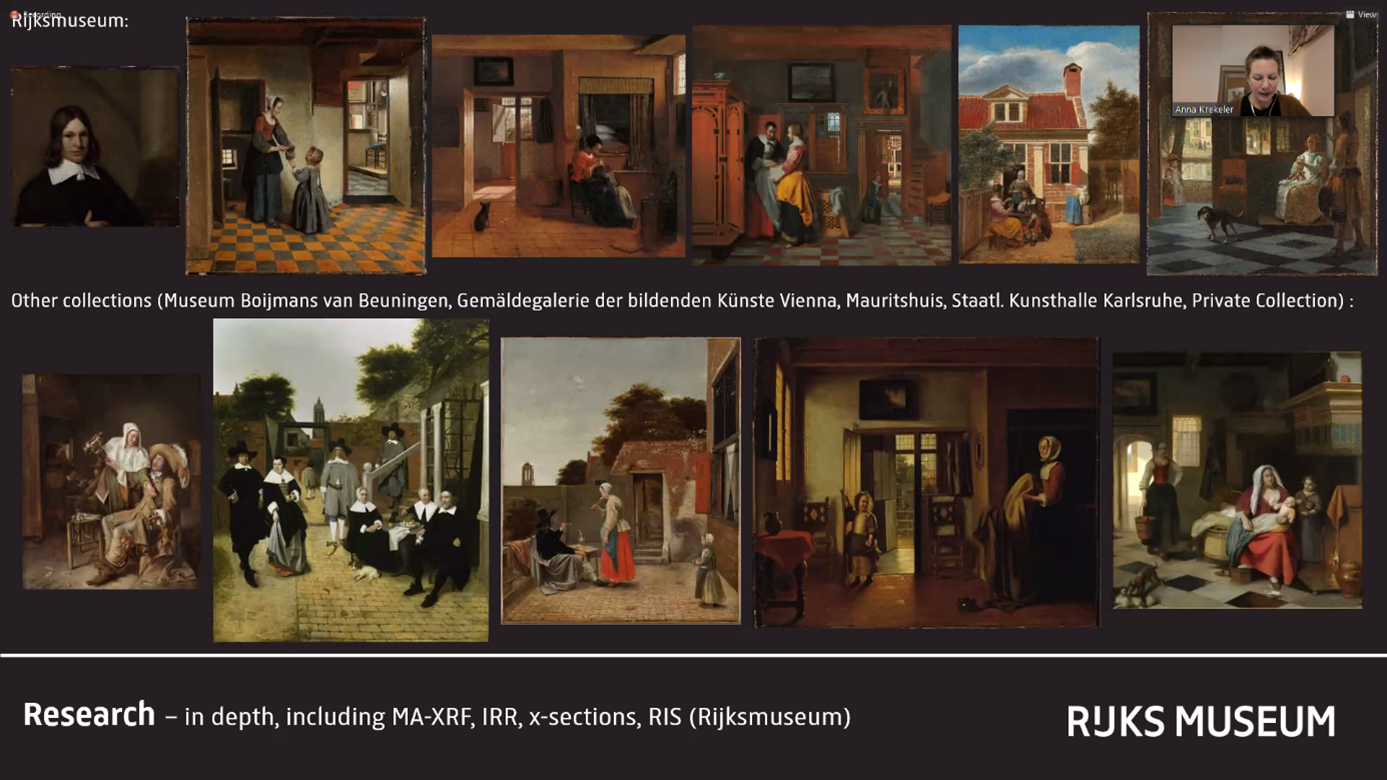

Screenshot from Anna Krekeler's online talk hosted by Icon Paintings Group – 11 paintings subject to in-depth technical examination

In her online talk, Anna Krekeler (Paintings Conservator, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam) focused on the recent research into Pieter de Hooch's painting techniques, an important contribution to technical art history and knowledge on historical Dutch painting. In total, 11 paintings from collections in Netherlands, Austria and Germany were subject to in-depth analysis using various non-invasive and invasive techniques, including X-radiography, IR reflectography, MA-XRF and RIS-VNIR/SWIR spectroscopy, light-microscopy (stereomicroscopy and HIROX 3D-microscopy), hi-res photography and paint cross-sections SEM/EDX microscopy and element analysis, FTIR molecular analysis, fibre analysis and dendrochronology. Krekeler also included study of existing literature and technical data on 27 paintings from all over the globe. Paintings have been examined bottom to top and data acquired is sorted chronologically (early period, Delft period and Amsterdam period). De Hooch worked on baltic oak panel and flax canvas supports of which at least 3 have been reused.

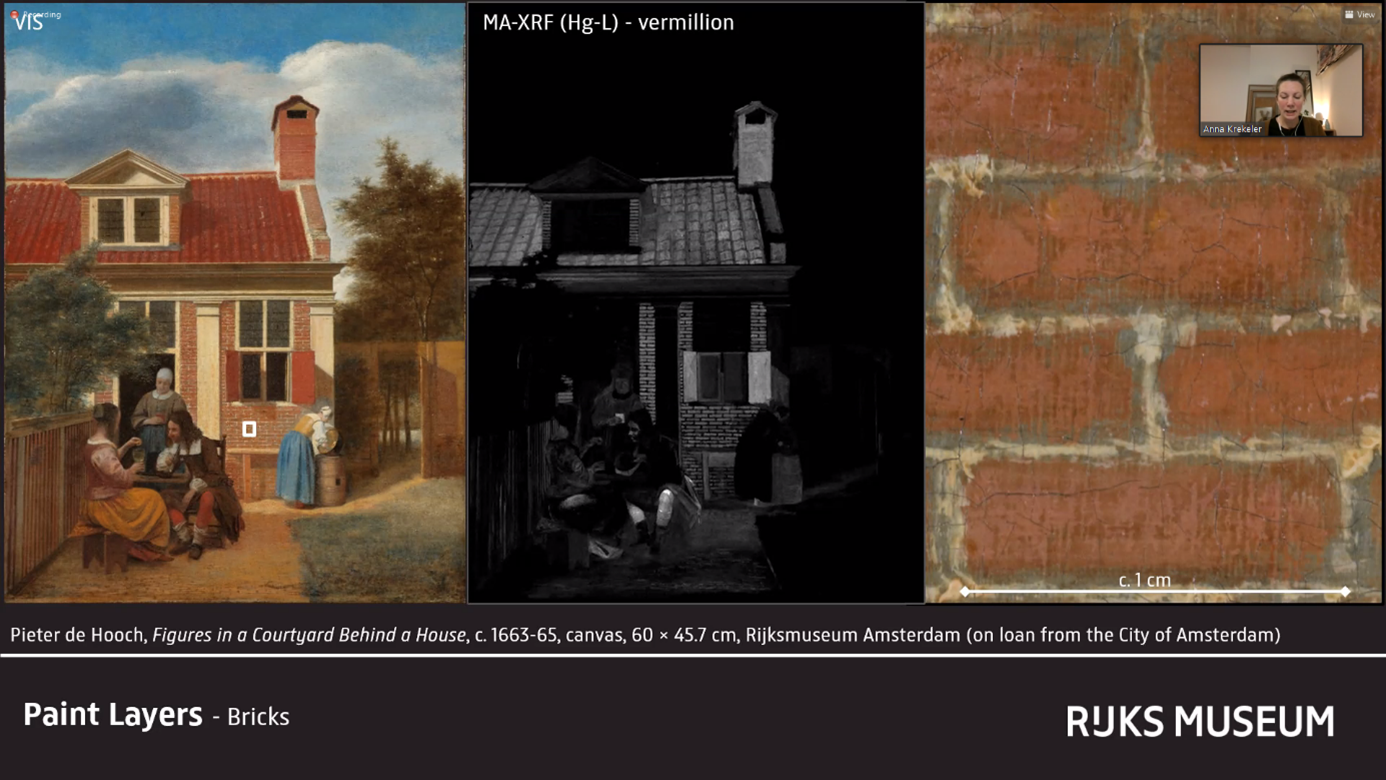

Screenshot from Anna Krekeler's online talk hosted by Icon Paintings Group – MA-XRF vermillion map and a detail of brickwork rendering

Preparatory layers changed through time and in relation to cities where he worked, from his early genre drinking scenes and his most iconic Delft interiors with tile floor renderings, brick buildings and courtyards to more dramatically illuminated scenes painted while living in Amsterdam. Mathematically correct use of central perspective is a constant. Many paintings show pin holes used for marking central vanishing points (sometimes more than one) and distance points. Underdrawing lines were made in a dry medium using a ruler for constructing a convincing perspective in his geometric interiors and exteriors, as Krekeler demonstrated through schematic representations. His brickwork depictions show remarkable details in colour and texture, ageing and weathering effects achieved through precise construction yet vibrant brushstrokes, leaving gray or red preparatory layers exposed to enhance realistic appearance.

De Hooch's ground layers for panel painting consist of a white layer or thin layers of chalk with a thin gray coating made from earth pigments and lead white. Gray and beige canvas grounds from his Delft paintings match preferences of his Delft contemporaries, Vermeer and Fabritius. In Amsterdam he opts for gray-over-orange double grounds and up to 3 layers of increasingly darker grounds. His palette is typical of the period, comprising lead white, lead-tin yellow, yellow lake, yelow earth, red earth, vermilion, red lake, umber, cassel earth, bone black, charcoal black, indigo, smalt, ultramarine, azurite and green earth as less common pigment for the period and geographical context. Characteristic of his work are many changes in the initial drawing and composition, all suggesting that he probably developed his designs directly on canvas.

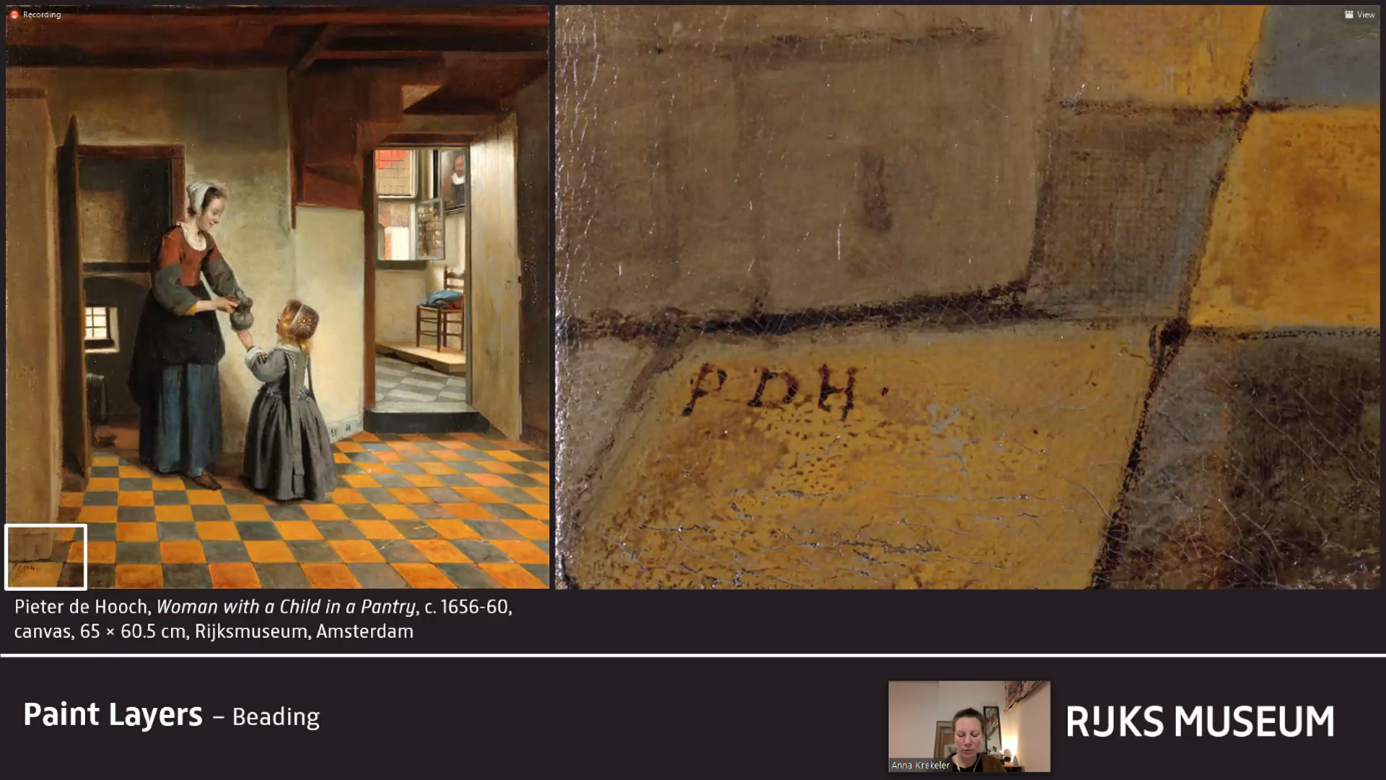

He sometimes used incisions to enhance tile joints and a transparent cassel brown glaze to achieve beautiful beading effects of ceramic tile glazing texture, signs of wear, or simply to add his signature. A question from the audience addressed this subject, wondering how this beading effect was achieved. Krekeler responded that he probably used a glaze rich in binding medium over already dried paint. Another participant asked if she was able to trace commissions and clients for his pieces, to reveal that only archival evidence of de Hooch collectors and owners is known to date. Clare Finn concluded the talk with an exciting announcement of Krekeler's talk on Vermeer in 2024, which prompted me to include some reflections on the two painters and recent related events.

In 2020, the exhibition on Pieter de Hooch by Museum Prinsenhof Delft has been nominated for an 'Exhibition of the Year' award by the renowned British art magazine Apollo, where an excellent essay on de Hooch by Kathryn Murphy was published, emphasizing his preference for space and pattern over rather formulaic figures as obstructions of geometric form.

Screenshot of the webpage of Museum Het Prinsenhof in Delft, venue of the retrospective exhibition Pieter de Hooch in Delft. From the Shadow of Vermeer showing the historical tiled floor similar to those captured on de Hooch paintings

Many conservation treatments and Krekeler's technical research data confirmed this, showing floor tile grids through transparent, aged oil paint upper layers of superimposed figures or pentimento silhouettes. As Murphy concluded: It is difficult to imagine a novel, a Girl with a pearl Earring, written in response to de Hooch. The Girl with a Pearl Earring best connoisseur, conservator Jørgen Wadum, summed up the vast research on Vermeer's technique and this tronie painting under a title This Girl is up for a dialog with everyone in the world, anticipating the recent brilliant public engagement initiative by the Mauritshuis, My Girl with a Pearl. Artists and art lovers from all over the world were invited to contribute their visual interpretation of the famed painting for interchanging display in an empty frame while the original Girl is on loan at the Rijksmuseum. The response was immense (I couldn't resist sending my own version).

Wadum often mentions the subtleties of Vermeer's brushstrokes and paint handling in rendering the girl's facial features and portraying her charisma. This enormous appeal of Vermeer's human depictions and obvious care invested in creating them is comparable to de Hooch's representations of architecture. His intimate interiors and vivid exteriors act as a main character for his paintings, while figures of people serve as artefacts with a role to accentuate architecture, the true pearl of his oeuvre. This is reflected in his dedication to details of built surfaces, as Krekeler elaborated while presenting the technique of this exquisite painter and, as she tentatively reminded, a bricklayer's son. Historical tiled floors of the exhibition venue and brick buildings of Delft certainly brought Pieter de Hooch's portrayed architecture of his time even closer.

Jelena Zagora

Zagora is a Paintings Conservator at the Croatian Conservation Institute and Associate Assistant Lecturer at the Arts Academy of the University of Split (Croatia).

She is a Secretary of the IIC Croatian Group.

Early 17th Century Bolognese Oil Sketches with Alice Limb (28 September 2022)

Review by Mackenzie Higgins (Paintings Conservator, Hirst Conservation)

On September 28th, 2022, I had the pleasure of attending Alice Limb’s talk on early 17th century Bolognese oil sketches. The presentation was based on research from her graduate thesis at the Courtauld Institute.

The talk mainly focused on a group of oil sketches by members of the Carracci family and disciples of the Carracci school. The Accademia degli Incamminati was established in Bologna in 1582, providing theory and artistic training under several of the Carracci family masters. Alice made the clear connection between oil sketches of the area and period, to the stylistic attributes of the Carracci influence.

Throughout the talk, she also discussed the significance behind artists’ materials, various supports, and explored some of the most likely purposes for these early oil sketches. This included their use as:

-

necessary practice pieces for artists, in which the Accademia worked with live models, which resulted in realistic practice sketches, where only the most useful examples would have been retained.

-

preparatory sketches, that would act as exploratory drawings to conceptualize ideas

-

character studies, which could be useful for future works

-

copies of other works, which is still a commonly used learning technique for artists to hone their technical skills

She went onto display Domenichino’s ‘Head of an Old Man’ which is a strong example of the generalized sketch types used for practice, or character studies. Sketches that were found to have specific likenesses, are thought to be used in preparation for commissions. Alice discussed how the Carracci’s works overlapped each other, using one another’s studies to inform their own pieces. This was furthered when she touched on pentimenti findings and examples of full reuse or reworking of sketches.

Alice addressed how 16th and 17th century artists would have chosen to carry out oil paint sketches on paper, due to the cheaper economic factor, the abundance of the material in the region, the standard sizing or ‘known size’ of paper, and the advantageous portability of the artworks. She also discussed the intense red ground often found in these pieces, as a direct result of the iron oxide pigment that was described as a ‘hallmark’ of these works, due to the wide elemental availability within the region.

She displayed Annibale Carracci’s ‘Head of a Woman’ to delve into practical and artistic intent behind the specific materials chosen. She discussed how material type and texture of support had significant impact on the visual appearance of these works and noted how much thought would have been given into the origin, cost, and implementation of the chosen materials. The ‘Head of a Woman’ sketch was a perfect example of this, as Alice pointed out that Annibale’s works were often done on the laid rougher side of the paper, likely due to the artist’s preference. She went onto explain that this rougher laid side of the paper was a result of the drying process, where indentations would remain on the papers that had been overlapped when drying. Meanwhile, ones without overlap would be in pristine selling condition. The indented papers were then sold at a lower cost, furthering the idea that artists would have had both aesthetic and economic motivations for choosing these substrates.

Another significant point of note was the impact of British grand tourists. She mentioned how these collectors would travel to Italy to acquire artworks to bring back with them, and how they were expected to learn from the Italian Masters. She drew attention to how this stylistically influenced British painters. Having these small paper sketches made it easier for collectors to transport. This level of portability contributed to the sketches being highly influential, despite their small scale and substrate.

This talk provided an insightful overview of the most likely purposes behind these early 17th century Bolognese sketches, and their importance of informing and influencing other artworks and artists. Alice offered valuable interpretations on the use of material, artistic decisions, and collector behaviour, which has all resulted in a wider impact for British painters and their artworks.

Mackenzie Higgins

Mackenzie is a UK-based Paintings Conservator at Hirst Conservation Ltd.

Born in Canada, she obtained a BFA (Hons.) with a Minor in Art History from Queen’s University, a Post-Baccalaureate in Art Conservation from SACI in Florence, and her Masters Degree in Conservation of Easel Paintings from Northumbria University.