Conservation in Action: How do you conserve an ancient landscape?

How do you conserve an ancient landscape?

Laura Ratcliffe Warren ACR

Lots of talking, biscuits – and upscale the tools! Although the principles of conservation and collections care hold true, transferring from a lab to a landscape I have had to trade my scalpels for scythes. Paid for by National lottery Heritage Fund for five years, the Penwith Landscape Partnership (PLP) has, amongst other things, the task of engaging community volunteers and landowners to help look after and promote this prehistoric living landscape. One of the oldest continually used farming landscapes in Europe, West Penwith in Cornwall is stuffed full of ancient sites and fantastic habitats (and cream teas!). This is a brief window into the unusual but satisfying conservation journey of working with a whole landscape.

Working in partnership

For many years I have been practicing archaeological conservation and mixed it with archaeological field work. When this job came along, I saw an intriguing opportunity to combine the two things. Normally, my conservation skills are restricted to objects and collections care either in the lab, on site or in museums. The PLP project saw a drastic upscaling from collection to landscape, and from object to monument - although from discipline to discipline within conservation, the principles and standards are of course fully transferable.

As is often the case with collections care, there is overlap with environment, owners, volunteers and the public - and this project is no different. The in-house project team is made up of a number of different landscape and environmental specialists and all our projects overlap. This is entirely satisfying professionally, as it means everything we do is more robust and often has multiple outcomes that help everyone.

A lot of what we do involves volunteers and working sympathetically within a special landscape both rich in monuments and ecological diversity. It is also a working landscape and all our projects aim to be sympathetic with the livelihoods and land practices of the farmers and landowners.

Community engagement

Our core workforce is community volunteers, and a key aim of the project was to train and upskill the community that lives within the area, and to foster a sense of ownership and responsibility. Folk join us for all sorts of reasons: an interest in the history of the area, a love of the outdoors, or wanting to connect to like-minded people. Three years in and we are now starting to work with local social prescribing networks, which is really exciting.

As well as the outside activity part of the project, we also have a historical research side to the job - I work with some of the volunteer team to improve existing site records and make new ones. This helps enable us to monitor conditions on sites as well as adding to the historic record of the county. Climate change in particular has meant more rain in Cornwall, and a lot of the sites we work on have been subject to changing water levels, which can damage them - making ongoing condition monitoring more important than ever.

I work closely with a small community group who already carried out some of this work, but as the area contains nearly 3000 recorded ancient sites, it’s a large task!

Reflecting on the bulk of my work to date, I have found a lot of what we do is making things more accessible for non-professionals. I think folk often see heritage management as something so specialist there is nothing that they can do themselves. I find myself frequently demystifying things and helping people see that really, they can do something themselves! And every small thing done contributes to the bigger picture, especially if everything is joined up.

Scythes not scalpels!

And here lies the upscaling part! A lot of the sites we work on are at risk of damage from vegetation, particularly bracken, either from the roots, which can disturb below ground features and break parts stonework or from the foliage which can completely hide some of the site, making them hard to find and care for. The discovery element is often the part the volunteers enjoy the most, revealing a site that hasn’t been seen for a very long time is entirely thrilling, and we have found a few new sites as we have gone along. We carry out surveys and condition checks, and take record photographs and 3D models as well as carry out hedging repairs on some Cornish Hedges – a heritage skill. All training is provided.

The tool of choice is often a scythe (more specifically a brush scythe as opposed to the long grass scythe) and accompanying six pack often associated with Cornwall’s popular Poldark. A lot of the area is heathland and moorland and the scrub and undergrowth is quite tough.

Scythes are not only popular but highly effective. As is often the case with conservation activities, the satisfaction of leaving a thing in better condition than you found it is a strong lure as well! As you can see from the picture below of Mulfra Hill barrows – the weather is not always fair, but we have fun anyway.

Volunteers scything in the mist on Mulfra Hill

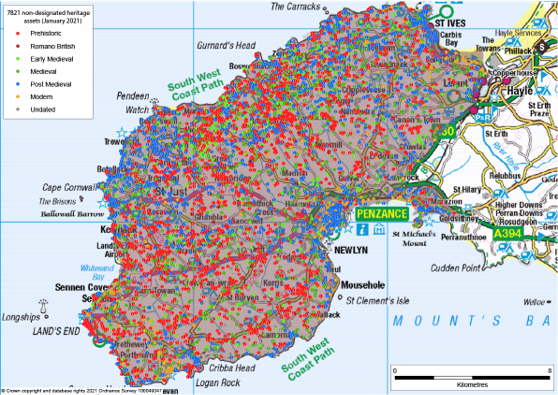

There is a huge number of heritage sites in West Penwith (7821 designated heritage assets, 261 being Scheduled Monuments and 2249 listed buildings), and we actively work on about 45. We re-visit them several times a year, and each time, the task is easier and the condition of the sites is improved. This makes it obvious that good ongoing care really works and gets easier every time. A legacy of this project will hopefully be a team of locals who would carry on this care.

Cup of tea and a nice biscuit

An awful lot of what we do is talking to people. Communication is so important within a community and between disciplines if things are going to work out. Whilst the work I do concerns historic sites, they often fall within a protected habitat or actively used farmland (often both), and with a slight tweak to something we do, we can benefit wildlife or reduce inconvenience to a farmer, sometimes even add value. For me this is exciting professionally and it often makes folk more open minded to things that benefit the heritage, historically seen as the problem area and to be ignored or avoided as too much trouble.

The legislations and advice covering heritage in a working landscape are complex and often don’t overlap well. Just being around to help translate things into useful or understandable terms or waymark folk to the right place has been very helpful for the success of my part of the project. Setting up meaningful and practical lines of communication is hopefully giving people in the area a better understanding of the heritage around them.

A happy side effect is that often, there is a family story or two or some unrecorded insight into the landscape, which enriches the story of the area. Taking note of these oral histories and disseminating information about the area on our website is the virtual equivalent to our on-the- ground communications.

Commissioning reconstruction drawings of some of our sites has been particularly engaging as often, folks just don’t know what they are looking at. Archaeological sites and monuments, especially if they consist of partially standing or buried areas can be quite hard to interpret sometimes!

Environmental benefit

As we clear and help manage vegetation on an ancient site, we often see a bursting forth of new wildlife as the more aggressive species are trimmed back.

In these times of climate crisis and pandemic, one does often wonder what role conservation and heritage can play other than to look back at previous periods of environmental turbulence. One unexpected connection for me here is the often-abundant biodiversity on ancient sites. The landscape of West Penwith does not lend itself to the planting of trees, as is often advocated as the way to help fight climate change.

The ancient Cornish Hedges of the county are havens of wildlife and the mystery surrounding heritage sites often means they are sheltered from too much land management through time, also lending them a sort of wildlife haven function. Helping to manage these sorts of sites means they can continue to contribute to a robust and healthy environment as well as helping ensure their continued survival as sites themselves.

Mulfra bluebells

And in one particular project, where climate change is causing irreparable damage to a cliff top site, we are working with the additional support of Historic England to help them develop their strategy for responding to site loss on coastal sites. We will be making a full record of the Medieval Chapel and hermitage of St Levan against its imminent loss from cliff fall and extreme rainfall runoff. An exciting opportunity coming out of a sad loss.

So how do you conserve an ancient landscape?

Well, it takes a village as they say. Scythes, biscuits and fostering a love of the land, this project has certainly been a deviation from the norm for me but entirely enjoyable!

Working with and enthusing the local community is fantastic, helping farmers care for the heritage on their land is also entirely rewarding. There are so many levels of communication to be taken into account, woven together into one inspiring vision for positive landscape care shared by many groups of people. One of my colleagues often says we are all carrot and no stick. And what a lovely place to be in a world where commercial decisions often shape the work we do! And if we can encourage a rare butterfly to flourish or have a nice cup of tea and a biscuit as we go- why not!

With thanks to the National Lottery fund for its support. The project runs for another two years. penwithlandscape.com

All images are © Penwith Landscape Partnership.

About the author:

Laura Ratcliffe Warren has a background in archaeological conservation, graduating 20 years ago from Cardiff University. She has since worked in museums, expanding her skillset to encompass collections care, then more recently returned to the archaeological arena taking on project-based contracts or working on a self-employed basis.

Conservation in Action

Conservation in Action is a follow-up project from the “Values of Conservation” research project, which identified and articulated the values of cultural heritage conservation to society. We now want to demonstrate these values through a series of Conservation in Action stories – they are one of the most effective advocacy tools at our disposal, due to their power to captivate stakeholders, policy makers and those less familiar with the sector.

Some of the Values of Conservation we discussed in our report are:

- Sense of place: Conservation supports healthy communities by preserving cultural heritage, which gives places their character, brings communities together and fosters pride of place.

- Volunteering :The conservation sector helps people build social connections through a range of volunteering opportunities that encourage individuals to work together in a positive atmosphere.

- Mitigation and adaptation: Conservator-restorers can provide knowledge and expertise to protect and conserve at risk heritage and to inform mitigation and adaptation responses to climate emergency.

- Climate change communication: Cultural heritage can be an accessible resource for communicating climate change, empowering people to confront the challenge and inspiring more sustainable lifestyles.

The Penwith Landscape Partnership project is a good example of how conservation can bring people together, build communities, and foster a sense of place - a a key aim of the project was to train and upskill the community that lives within the area, and to foster a sense of ownership and responsibility to the land.

The environmental benefit is just as clear: as the vegetation is cleared up on the ancient site, there is often a bursting forth of new wildlife. Moreover, each time the site is visited for upscaling, the team find that its condition is improved and the work is easier. Finally, as PLP are working with the support of Historic England to develop a strategy for responding to site loss on coastal sites, we see that conservator-restorers can provide knowledge and expertise to protect and conserve at risk heritage and to inform mitigation and adaptation responses to climate emergency.

Have a project you want to share with the world? Get in touch!