Taking a Closer Look at the Royal Pavillion's Chinese Wallpaper

In May 2020, I successfully applied to the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, in what has now become Part I of the Chinese wallpaper project.

Part I was a great opportunity for me to take a closer look at our wonderful Adelaide corridor at the Royal Pavilion but, with Covid restrictions in mind, the project was initially about how to make this wallpaper more accessible online to reach a wider audience.

Online content will be available later this year, but here is a sneak preview of the work so far.

The Paper

This fantastic 18th century hand-painted wallpaper, produced in China for export to Europe, is remarkable for its longevity as much as its spectacular scenes, and also for having survived in its original location since being hung there two hundred years ago - one of very few items in the Royal Pavilion which have remained undisturbed in this way.

We refer to this wallpaper (which depicts a hunting scene, lantern festival and Dragon Boat festival) as the Adelaide Corridor paper, since the passageway where it is located links the Queen Adelaide tearooms, and the suite was used by Adelaide when she became Queen on William IV's accession in 1830.

The Adelaide corridor and the rooms leading from it were part of the so-called ‘New North Building’, the last major portion of the Royal Pavilion to be built. It was completed in 1821. Senior members of the royal household had apartments there and some rooms were occupied by Lady Conyngham, mistress to the King.

Wallpaper, especially hand-painted paper, was expensive and highly valued. It was often attached to linen or canvas so that it could be moved, stored and replaced elsewhere.

However, the Adelaide Corridor paper was pasted directly to the walls without such a fabric lining. The corridor ceiling height is quite low and, as this export paper was made to a standard height, it was shortened in such a way that the tops and bottoms were retained. All the ‘cutting and pasting’ needed to make this wallpaper fit the space may account for its very firm attachment to the wall and consequently to its survival in situ: a rare example, as almost all the interior decorations of the Pavilion were removed prior to the 1850 sale of the building by Queen Victoria.

The Condition

The wallpaper was varnished at some time in the late 19th century and while this may have protected it from some types of damage, it has certainly resulted in the brown staining that can be seen today. In the 1960s the paper was cleaned but some of the varnish seems to have sunk into the paper, leaving local staining as well as brittleness.

The paper also suffered damage through rainwater leaks and the effects of oil and candle lighting.

During the 20th century, a bamboo trellis pattern paper was hung over some of the damaged areas, which are still there, waiting to be revealed.

Between 1914 and 1916 when the Pavilion served as a military hospital, this part of the building housed Indian Officers’ quarters. Between the 1920s and 1960s, it became family accommodation for the Director of the Pavilion. It is recorded that the children of the last Director to occupy these rooms, Clifford Musgrave, would ride bicycles up and down the corridor. Given such uses over the years the wallpaper has been scraped and bashed about quite a bit; at less than two metres wide (5’ 4”) that isn’t too surprising.

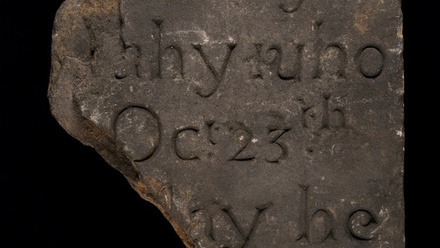

More surprising are some of the pencil additions to the wallpaper, noticed during the recent examination. Which past guest might have been responsible?

The wallpaper was glazed with perspex in the mid 1970s and in the late 1980s this was replaced with the more robust glazing system you see today, and has remained undisturbed since that time.

The main aim of this project was to enable the wallpaper to become more accessible through online content - these required photography and research. To read more about the methodology of the project and next steps, check out the full article in the December 2021 issue of Icon News (p. 24)