Conservation reveals fascinating details about Queen Victoria’s rediscovered Japanese screen paintings

A pair of folding screen paintings sent to Queen Victoria in 1860 as part of a dazzling and historic diplomatic gift from the Japanese shōgun (military leader), and thought not to have survived to the present day, has been rediscovered in the Royal Collection.

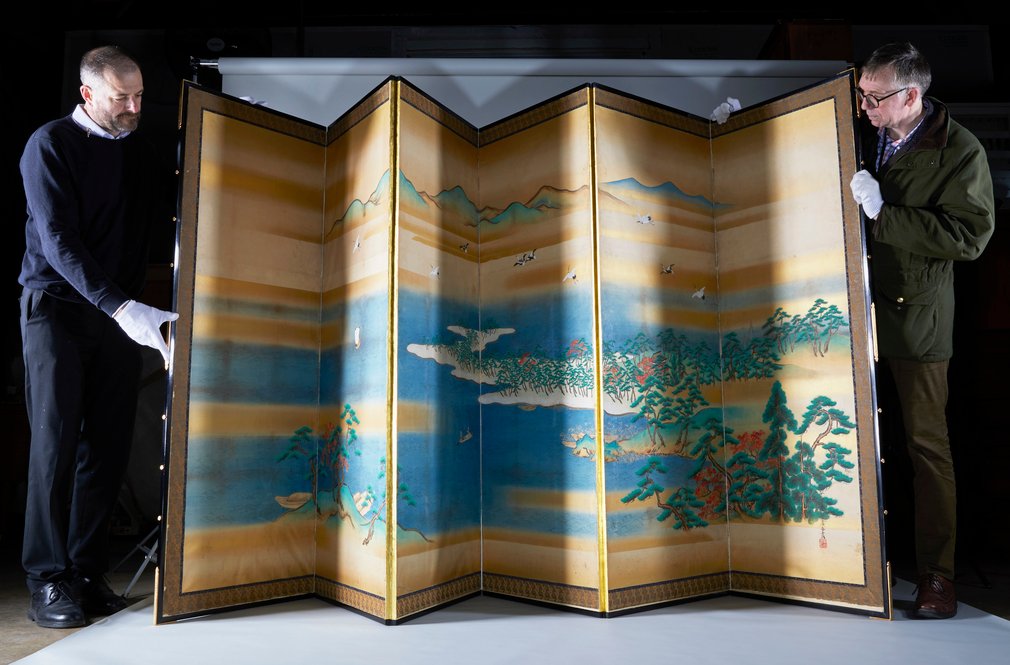

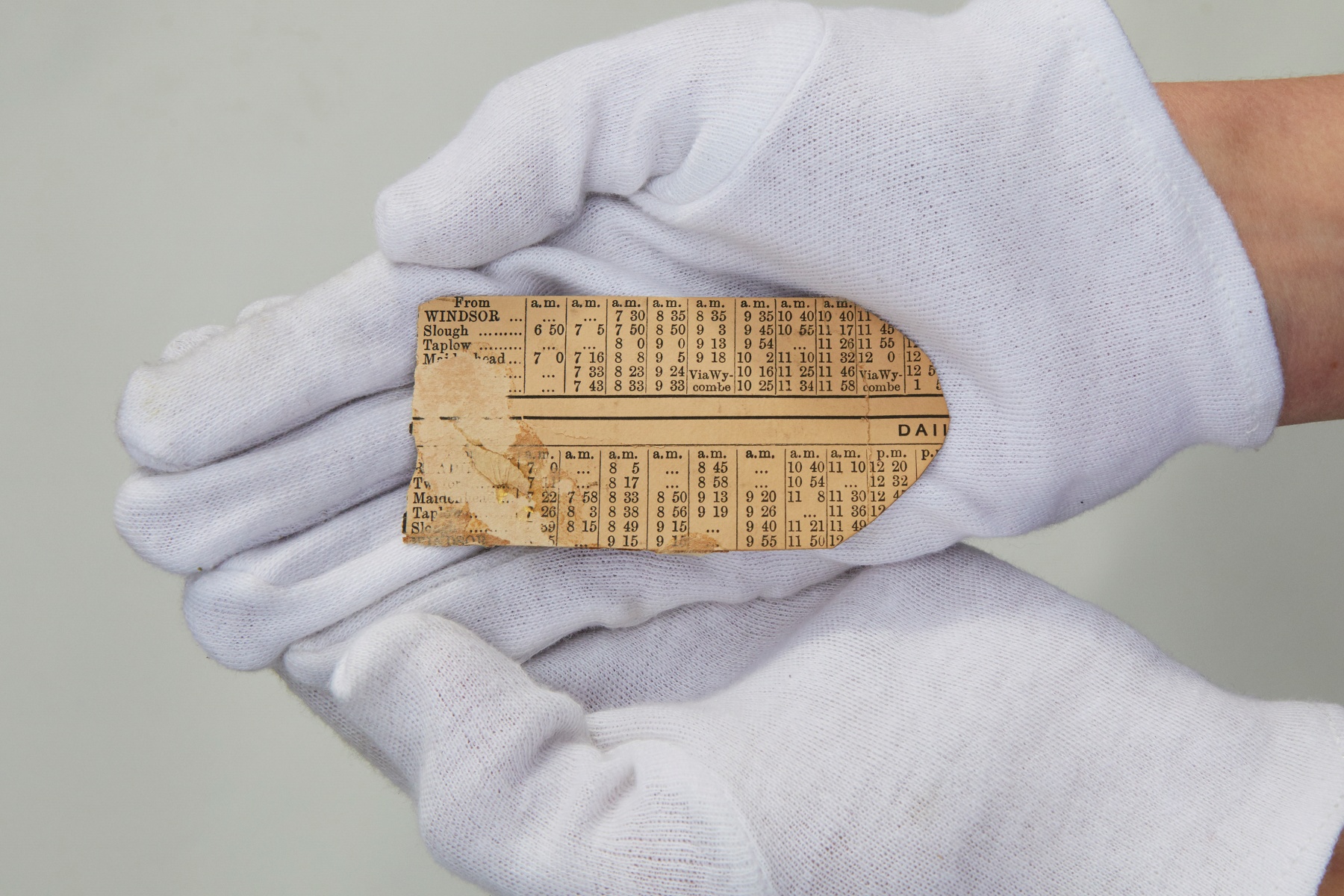

Extensive conservation work following the discovery has revealed fascinating details about the screens’ history, including how they were hastily produced after a dramatic fire in Tokyo destroyed the original versions, and how wear and tear was patched up at Windsor Castle in the 19th century using fragments of Victorian railway timetables.

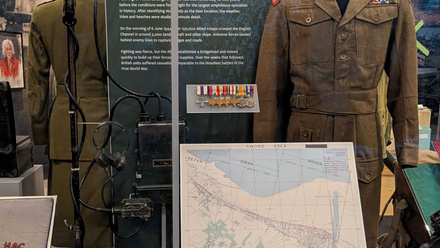

The screens will go on public display next month for the first time since they arrived at the British Court 162 years ago. They will form part of Japan: Courts and Culture, the first exhibition to bring together the Royal Collection’s holdings of Japanese works of art, opening at The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace on Friday, 8 April.

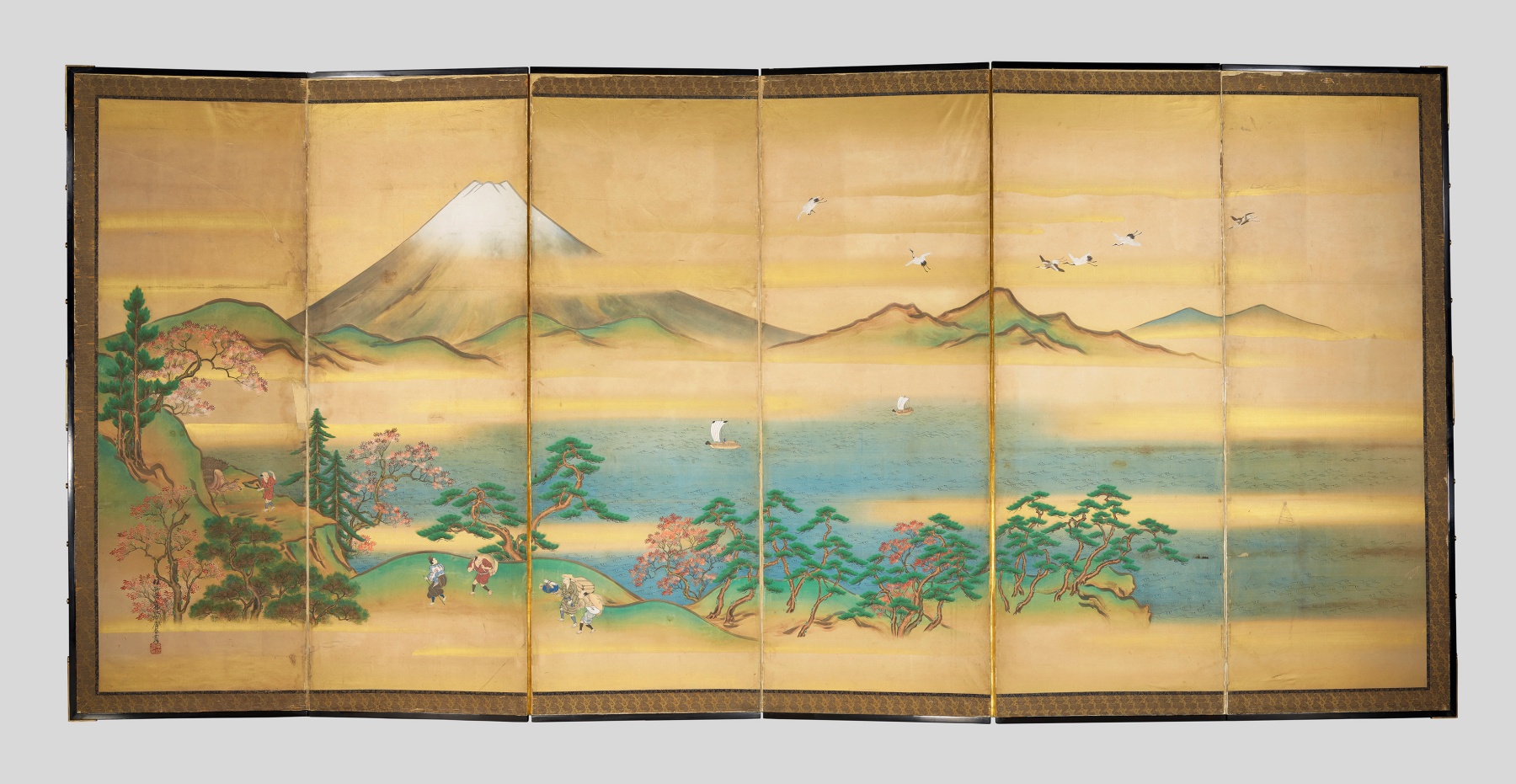

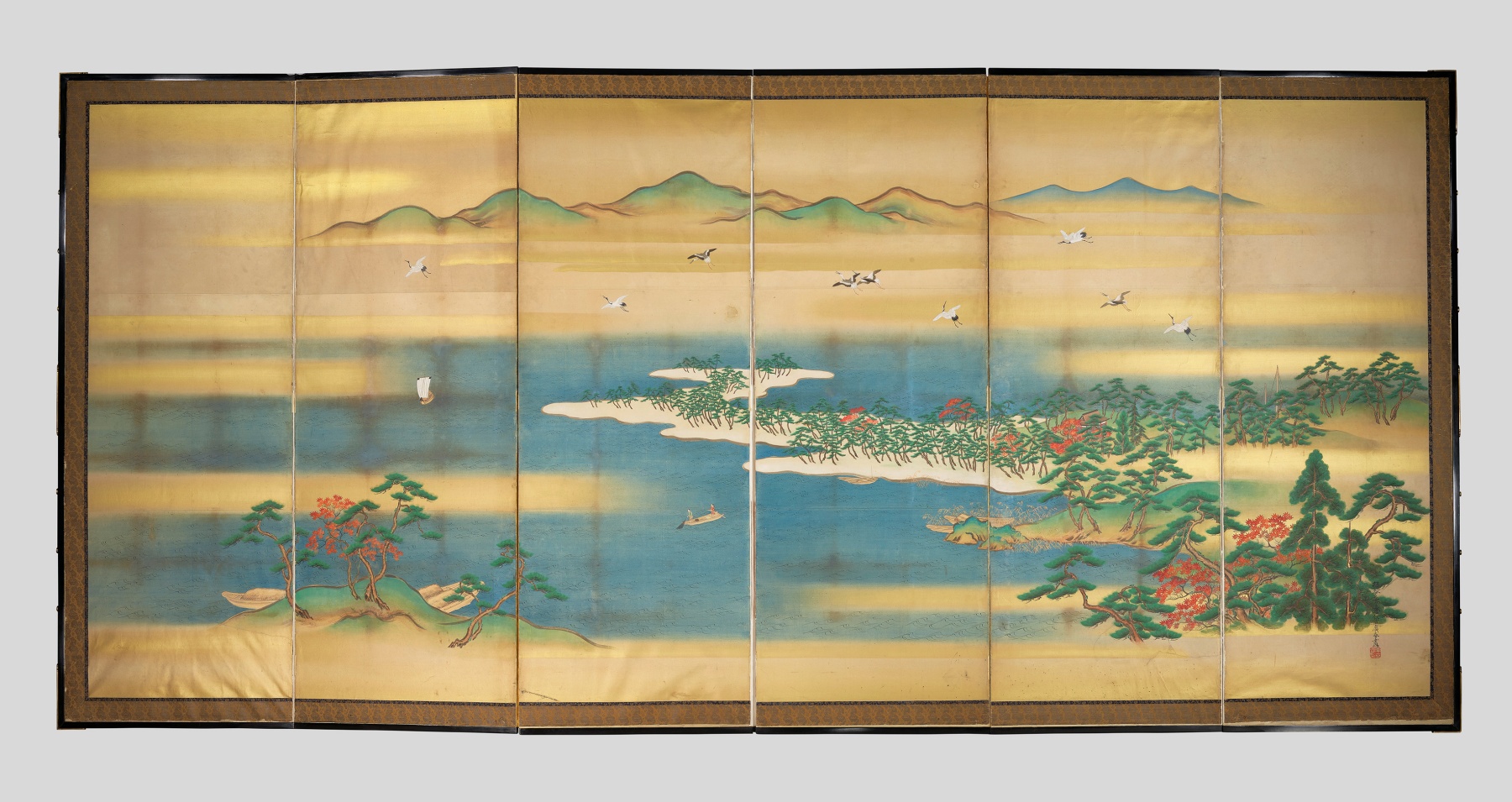

The screen paintings, which depict the changing seasons in exquisite detail, formed part of the first diplomatic gift between Japan and Britain in almost 250 years.

They were sent by Shōgun Tokugawa Iemochi shortly after Japan’s dramatic re-opening to the West, following more than two centuries of deliberate isolation.

The lavish gift to Queen Victoria marked a landmark treaty that reopened seven Japanese ports and cities to British trade and allowed a British diplomat to reside in Japan for the first time. Folding screen paintings – a choice Japanese diplomatic gift since the 16th century – were an ideal vehicle for showcasing the painting skills of the finest court artists of the day. Also included in the gift were a set of lacquer furniture, spears inlaid with glittering mother of pearl, and swords by leading court swordsmiths, all of which will also be on display in Japan: Courts and Culture.

Eight pairs of screen paintings were sent to Queen Victoria as part of the gift, but none were thought to have survived to the present day.

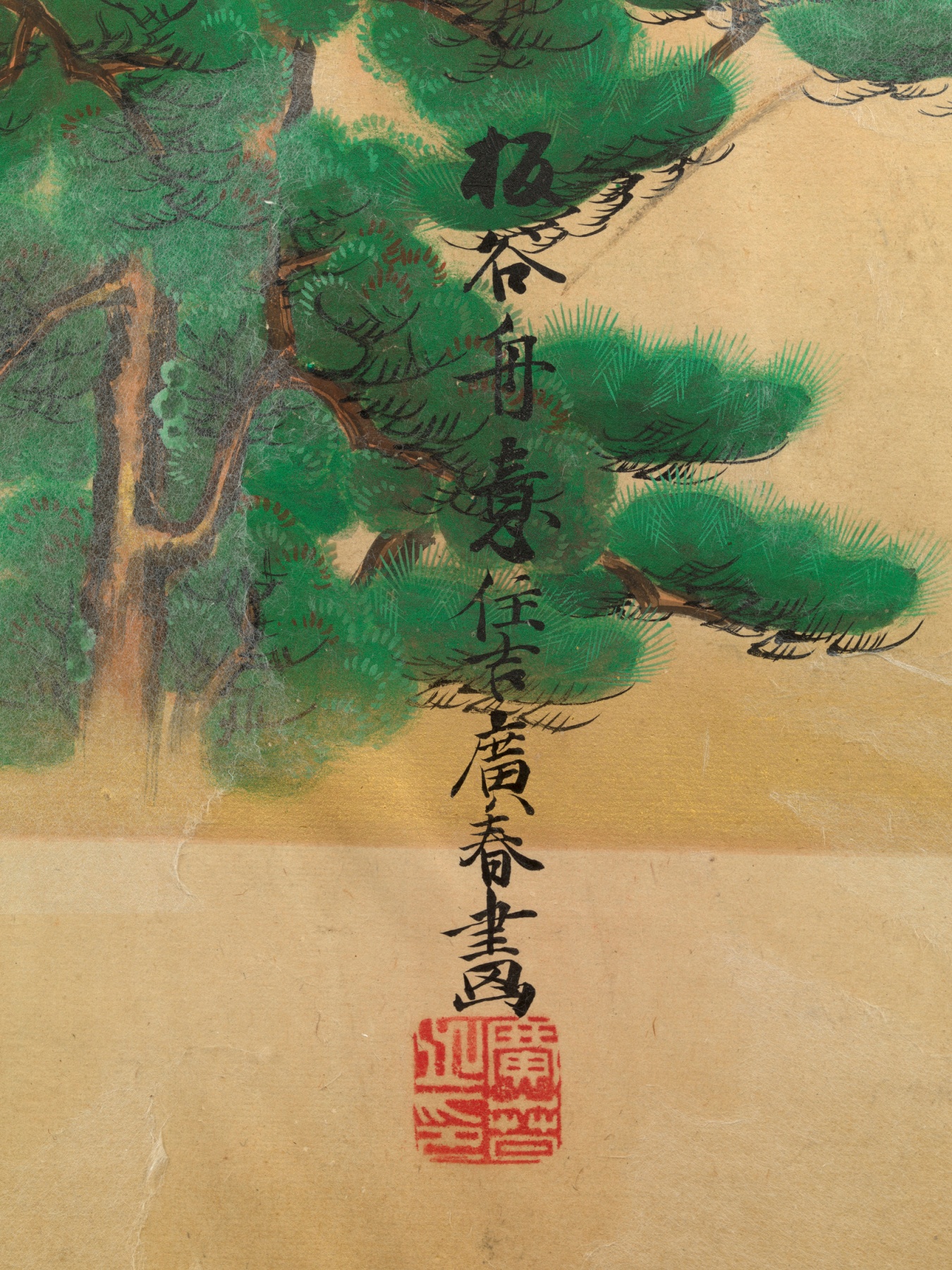

However, research for the exhibition by Royal Collection Trust curators raised the possibility that some might still exist in the Royal Collection. In 2017, Dr Rosina Buckland, Curator of the Japanese Collections at the British Museum, was able to translate the artist’s signatures on the two screens in question.

The signatures, and further research by Royal Collection Trust curators to compare the screen paintings with those received by other European monarchs at this time, revealed that they were the work of Itaya Hiroharu, one of the artists likely to have worked on the gifts for Queen Victoria. Sometime after their arrival in Britain, the screen paintings had simply been catalogued as Japanese works by an unidentified artist, and their link to the gift from Shōgun Iemochi – and so an understanding of their historical significance – had been lost.

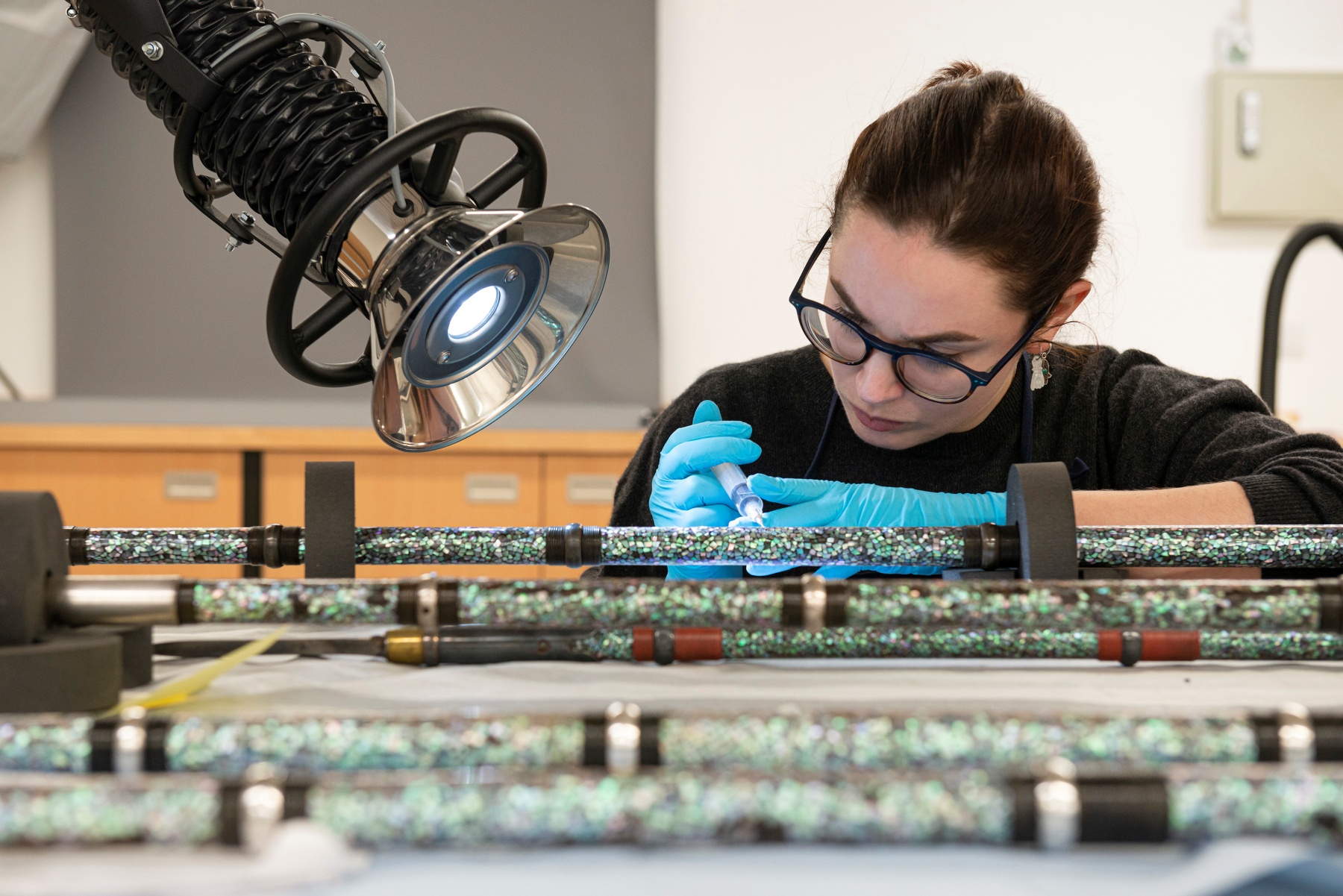

Both screens have undergone conservation treatment due to their age and fragility

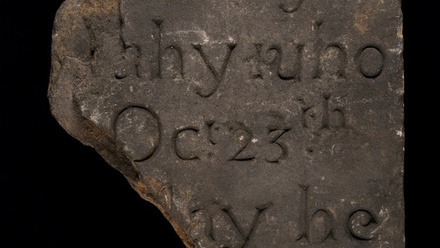

During treatment, specialist conservators discovered fragments of a Victorian railway timetable securing torn areas on the reverse of the screens. These historic repairs suggest the screen paintings were regularly used and admired at the British Court. The stations listed in the timetable begin at Windsor, which indicates that early repairs may have taken place at the Castle there. The train timetable was probably used because replacement Japanese paper was not readily available at the time.

Conservators also found that painted silk panels had been mounted on fewer layers of paper than was usual in 1860. Screen paintings of this kind are usually mounted on six to nine paper layers; this pair had just two or three each, which meant that acidic content from the inner wooden frames had discoloured the painted silk over time.

The reduced number of layers was likely because the paintings had to be mounted very quickly: in November 1859, a huge fire broke out at Edo Castle in what is now Tokyo, destroying the completed paintings. Replacements had to be hastily commissioned and prepared for dispatch to Britain at short notice.

Conservators also found that the painted silk panels had been mounted on just two to three layers of paper, rather than the usual six to nine, allowing acidic content from the wooden frames to discolour the painted silk over time. This was likely because the paintings had to be mounted very quickly: on 11 November 1859, a huge fire broke out at Edo Castle in what is now Tokyo, destroying the completed paintings. Replacements were hastily commissioned, but just weeks later the screens’ original artist, Itaya Keishū Hironobu, died and the work had to be passed to his pupil, Hiroharu.

The painted paper panels have been completely remounted. In the process, old linings and old repairs were removed, and tears were repaired and infills applied. Inner wooden frames supporting the paintings were cleaned and smoothed.

After this, paper conservators covered each side of the lattice frames with six layers of conservation grade Japanese tissue. These layers will protect the paintings from the wooden core and protect against damage caused by the natural movement of paper due to fluctuations of temperature and relative humidity.

You can find out more about the conservation work here.

Rachel Peat, curator of the Japan: Courts and Culture exhibition, said:

After decades of believing these important gifts were lost, this rediscovery is extraordinarily significant. The screen paintings marked a new era of diplomatic engagement between Japan and Britain and brought the vivid beauty of Japan’s changing seasons right to the heart of the British Court.

Japan: Courts and Culture is at The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, 8 April 2022 – 26 February 2023.