I am an Accredited Stained Glass conservator at Barley Studio, York, with 10 years of studio experience since completing my studies at the University of York (during which I was awarded the inaugural Nicholas Barker prize for my dissertation research). As the specialist conservator within the Barley Studio team, working alongside Managing Director and Head Conservator Keith Barley, I have responsibility for ensuring that all conservation work is carried out fully and documented appropriately.

As a conservator my aim is to make a difference to the objects in our care, either now or for the future; to clean, to improve the appearance if possible and appropriate, to preserve from future deterioration through the installation of environmental protection. I undertake glazing surveys, giving advice on the care of stained glass in private collections, churches and cathedrals across the UK. Since 2017 I have been a member of the Stained Glass Committee of the Church Buildings Council.

Working at Barley Studio I have had the privilege to work on many interesting projects, from individual windows in homes and parish churches to major historic glazing schemes, including the world-famous sixteenth-century ‘Herkenrode’ glass at Lichfield Cathedral and the beautiful fourteenth-century glass of St Denys' Church in York.

Lichfield Cathedral, Staffordshire: Conserving and Protecting the ‘Herkenrode’ Windows

Between 2010 and 2015, Barley Studio conserved and protected nine sixteenth-century stained glass windows, each approximately 11 m high, seven of which were originally made for the Abbey of Herkenrode, Liège.

Date completed : 31 January 2015Duration : 240 Weeks

The opportunity to conserve this magnificent stained glass arose due to the need to restore the surrounding stonework, which was badly eroded and no longer able to support the glass; all of the windows were removed to facilitate the stonework repairs.

During the project we were privileged to collaborate with stained glass historians from the Belgian Corpus Vitrearum Medii Aevi (CVMA), Yvette Vanden Bemden and Isabelle Lecocq, who regularly visited Barley Studio to study the Herkenrode windows as they were being conserved. A joint publication by the English and Belgian CVMA on these beautiful and important windows is planned.

As we examined the glass we were astonished at the remarkable completeness of the original artwork, due to its long history of minimal and sympathetic restoration. Indeed, we believe that the Herkenrode windows in Lichfield comprise more original sixteenth-century glass than survives in present-day Belgium.

Barley Studio’s conservation approach has continued this tradition of minimal intervention, whilst also introducing some innovative conservation techniques. The nineteenth-century leadwork of the panels was still in good condition and quite sympathetic to the glass, and so we decided not to dismantle and re-lead the windows, thus avoiding much danger to the historic glass. Instead, many mending leads were reduced or removed completely by shaving away the surface leaf of the lead calme, greatly reducing the visual intrusion of these leads and helping to bring forward the original design lines.

The glass painting shows the remarkable skill of the Renaissance artists, with layers of delicate shading combining different colours of grisaille paint. However, in many areas the detail has faded due to corrosion of the glass and paint, caused by condensation on the internal surface. Developing another innovative conservation technique, we restored some of this lost painted detail by painting on the reverse of the glass using a cold (unfired) paint; a simple, effective and completely reversible intervention.

It has only been possible to undertake these conservation innovations because when the windows were re-installed, they no longer had to act as the weather shield for the building. Our new external protective glazing, fabricated from our specially kiln-distorted (Barley Bent) glass and installed in the original glazing groove, keeps the building water-tight. The historic glass is now supported in site-specific manganese bronze frames, fabricated in-house in our metalwork department, and fixed to the inside stonework. Internal ventilation effectively prevents condensation on the historic glass, helping to preserve both our conservation work and this wonderful artwork for many generations to enjoy in the future.

Stow Minster, Lincolnshire: Restoring the West window

The early twentieth-century West window of Stow Minster, Lincolnshire, was almost destroyed when it was blown out in a storm in January 2014. Barley Studio conserved the surviving pieces and restored the window back to its former appearance, reinstalling it with a new and much improved support structure.

Date completed : 30 June 2017 Duration : 48 Weeks

In January 2014, the 2.4m wide oculus West window of Stow Minster was blown out of its opening during a severe storm, falling nearly 10 metres and shattering into hundreds of pieces on the Minster floor below. Over the following days, the remains of the window (glass, lead and supporting metalwork) were collected together. Remarkably, one of the nine panels making up the circle was almost intact, although others were so badly damaged as to be unrecognisable.

After long discussions between the parish, their architect and their insurers, Barley Studio were commissioned to restore the window as far as possible to its original appearance. The window had failed due to the inadequacy of its original structural support system (ferramenta); therefore the design of a new and improved support system was an integral part of the reconstruction.

The window depicts Christ blessing the children, and is probably by Kayll & Co of Leeds. A plaque on the wall below states that “This circular window is erected in affectionate remembrance of Joseph Haydn Skelton (late of Stow Park) who died 15 December 1922”. We were fortunate to be able to source a high-quality photograph of the window before the damage from Gordon Plumb, which proved extremely useful to the restoration project.

The collected glass fragments were painstakingly pieced together, like a giant jigsaw puzzle, in order to save as much as possible of the original material, and to collate all available evidence for the original appearance. There were some remarkable survivals; large glass pieces, including several of the heads and areas of drapery, that were complete and in perfect condition. Other areas, such as the head of Christ and much of the lower third of the window, were so badly damaged that only small sections could be identified from the tiny fragments remaining.

The original cutline (leading pattern) of the window was reconstructed from the identified glass pieces, with the aid of the Plumb photograph. Where possible, broken pieces were edge bonded together using conservation grade (CAF3) silicone adhesive. Where areas either could not be found or were too badly damaged to reinstate, new painted pieces were created. The glass colours were matched as closely as possible from our own glass banks of mouth-blown antique glass, as well as glass sourced from Tatra and Lamberts glasshouses. The painted detail was faithfully recreated by copying surviving fragments where possible and following the original style where reconstruction was necessary.

In June 2017 the restored window was reinstated into the original glazing groove with the support of a new ferramenta system fabricated in black powder coated stainless steel, replicating the configuration of the previous bars, but in much more substantial square section bars and bolt fixed together.

This was a challenging but hugely enjoyable project for Barley Studio, requiring all of our investigative and restoration skills.

The Vice-Chair of Stow Parochial Church Council commented “The restoration of the window has been hugely impressive. We were amazed at the skill of the whole team in using a far greater proportion of the original glass than we could ever have envisioned, and the dedication to matching the original design and colours when fashioning new pieces. The finished window is a testament to the restorers’ craftsmanship.”

All Saints Church, Low Catton, York: Conserving and Protecting the Morris Company East Window

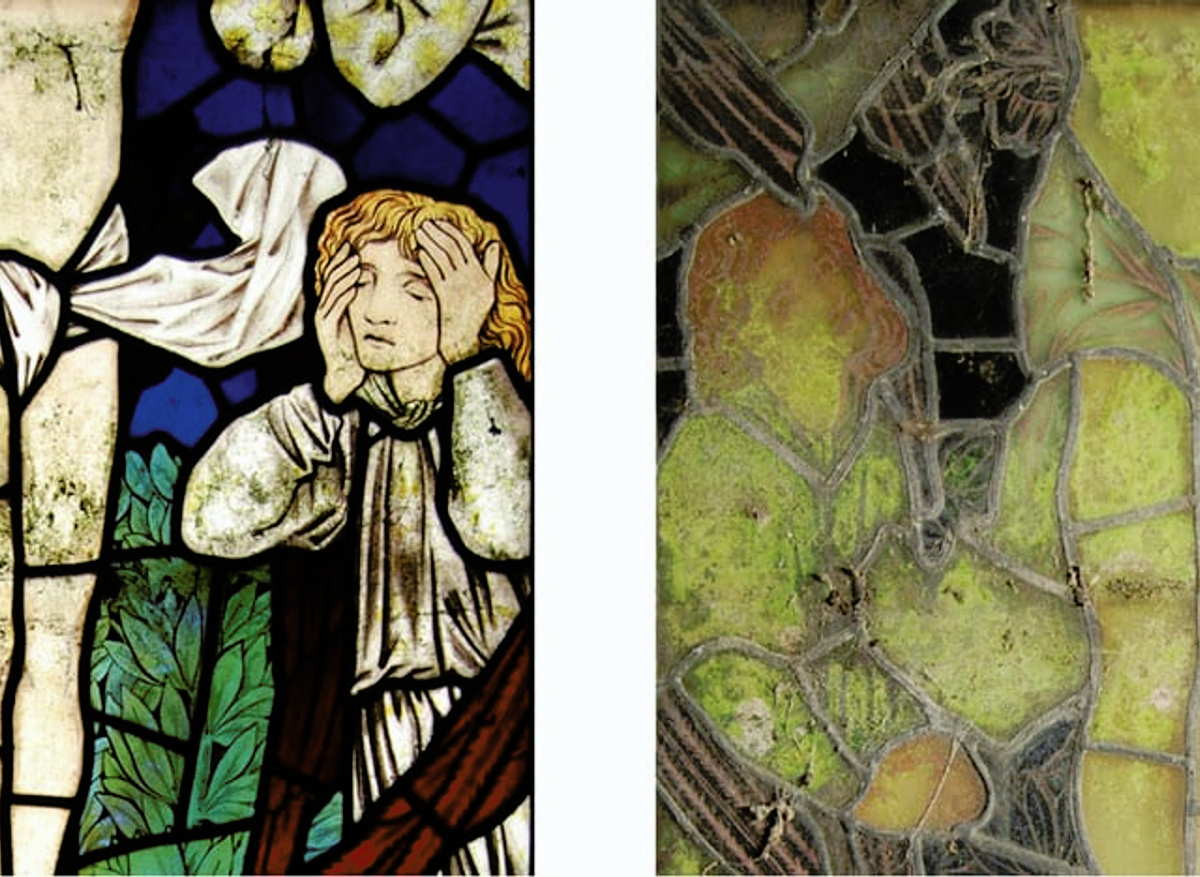

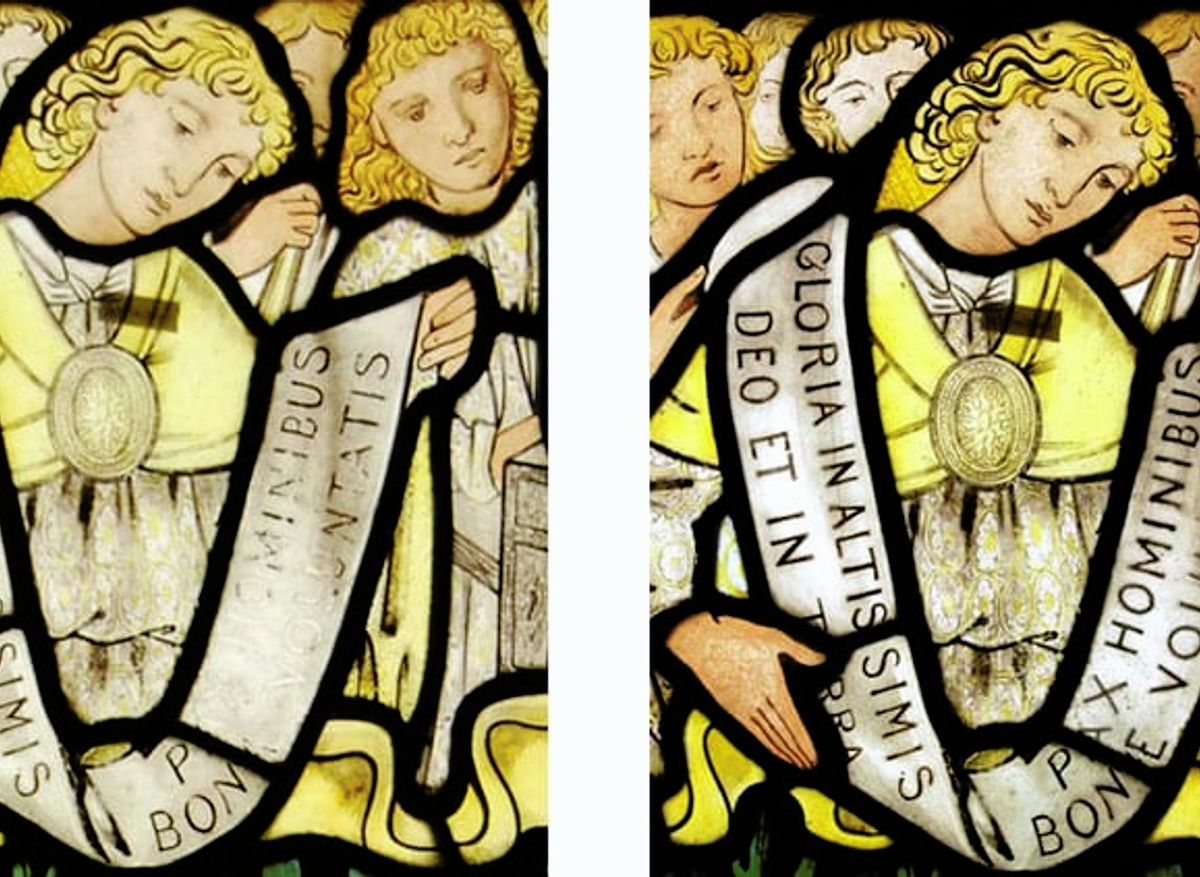

This beautiful nineteenth-century window by the Morris Company was covered in green algae, which was exacerbating problems of paint loss. The window was removed, carefully cleaned and reinstalled with internally ventilated environmental protective glazing (EPG) to keep the glass dry and prevent future algal growth.

Date completed : 30 November 2011 Duration : 24 Weeks

All Saints’ Church, Low Catton, dates back to the twelfth century, with additions in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. It was restored by the architect GE Street in 1866, during which the fine East Window by William Morris & Co was installed. The window, described by the Morris expert AC Sewter as “One of the most dramatic and emotionally intense of the firm’s early windows” was made to cartoons by Edward Burne-Jones (figure panels) and Philip Webb (tracery patterns).

The main challenges presented by the window included heavy deposits of green algae on the glass (due to damp conditions in the church), some loss of the painted detail (most likely due to under-firing of the paint, but exacerbated by the damp conditions) and damage to the outer borders of the panels (due to settlement of the building, causing the stonework to open out, in turn pulling and tearing the stained glass panels). The most important intervention, therefore, was to reduce the effect of the damp surroundings to keep the stained glass dry and prevent further paint loss and algal growth.

The window was re-instated with external environmental protective glazing, with the interspace ventilated to the inside of the building, providing ‘isothermal’ (dry) conditions for the stained glass. The use of external protective glazing protects the stained glass from the weather, and removes the need for the stained glass itself to form the climatic barrier for the building. This in turn makes possible further conservation interventions, such as reinforcing faded painted detail in key areas of figures and inscriptions by ‘cold painting’ on the reverse face of the glass.

Cold paint mixed from traditional glass pigment with gold size and distilled turpentine has good paintability and is reasonably robust to water and scratching once dry, whilst remaining easily removable using an organic solvent such as ethanol. This is a simple, effective and reversible technique which can substantially enhance the appearance of windows suffering from loss of painted detail.

The stained glass was framed in manganese bronze and screw fixed to the stonework, with the new protective glazing of kiln-distorted (Barley Bent) glass fixed into the original glazing groove. Framing the glass in this manner gave a further advantage of protecting the glass from any further movement of the stonework, whilst allowing the glass to be easily removed in the future should repairs to the stone become necessary.

Biography

Dr. Alison Gilchrist ACR