It tells us about the conservation of an Egyptian Mummy, a star item in the holdings of Perth Museum in Scotland. The hieroglyphs on the coffin lid reveal that it was made for a priestess who served in the Egyptian town of Akhmim.

Whether the present occupant of the coffin is the original one may be questioned . But whether she is or not, we know that she was around 35 years old and had poor teeth! Life wasn’t kind to her after death either, as the damage to the mummy makes clear. Of course, in the safe hands of the Perth team much has been done to stabilise the coffin and its contents and their work was undertaken under the interested gaze of a very interested public. Fortunately, most of the work had been completed by the time the exhibition was closed prematurely because of the pandemic. But crowd funding continues as there is still plenty of research to be done, which you can now contribute to here.

Lynette Gill

Icon News Editor

THE PERTH MUMMY

Anna Zwagerman ACR, Mark Hall and Will Murray ACR on saving the Perth Museum’s Mummy

The city of Perth is undergoing a large-scale cultural transformation and one of the capital projects undertaken is the conversion of an old concert hall in the city centre, known as City Hall, into a new museum. At the moment only 0.05% of the collections at Perth Museum & Art Gallery are on display. The new museum will offer the opportunity to show many more objects, including several star items that have not been exhibited since the 19th century.

ABOUT THE MUMMY

One of these star items is a Mummy and its coffin. In 1896 a businessman from Alloa bought them from the Cairo Museum, and donated them to his local museum. When this museum was closed down in the 1930s the collections were dispersed and Perth Museum was offered and accepted the Mummy and coffin. They were exhibited through into the 1970s, when it became apparent that their condition was too fragile to continue permanent display.

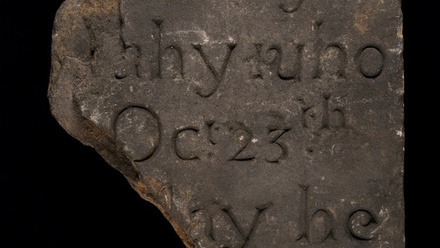

In 2013 the Mummy and coffin were taken to the Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital, where they were X-rayed and CT scanned as part of a Manchester University Bio-bank project. The research revealed that the Perth Mummy was female, approximately thirty-five+ years old when she died, and had poor dental health. The imaging techniques also showed severe internal damage with broken and dislocated bones in her chest and abdomen. This seems likely to have happened during an ancient grave-robbing episode in search of amulets concealed within her bandages.1 The hieroglyphs on the coffin lid revealed that it was made for a female named Ta-Kr-Hb, who served as a priestess in the Egyptian town of Akhmim.

The Mummy is a strong favourite with local visitors. Despite not having been on permanent display she is regularly asked after, and grandparents are keen to show their grandchildren Perth’s famous Egyptian Mummy. An opportunity arose through the City Hall engagement programme to put on a conservation in action exhibition in one of the museum’s galleries. This enabled a long-standing plan to conserve the Mummy in public to be put forward as the highlight for display, and the exhibition was built around her treatment.

CONSERVATION PLAN

The CT scan showed that the Mummy’s chest and pelvis area were completely jumbled. Her back was torn open, and there were bones lying in the bottom of the coffin. At the area around her ankles the wrappings were badly torn. Much of the damage appeared to have occurred in antiquity, when a lift of the body was attempted. This we thought was unsuccessful due to the attachment of the mummy to the coffin base, likely by the resins used in her wrapping process.

A large fragment of timber was detached from the foot of the coffin base, and a long strip of timber was detached on one side. The cartonnage was generally quite damaged, and much of it missing. The coffin lid was heavily soiled, and in many areas the cartonnage was lifting.

Will Murray ACR of the Scottish Conservation Studio proposed the following conservation treatment:

- Photograph and record the current condition

- Surface clean

- Remove, store and/ or reattach loose material

- Loosen the Mummy so that it is no longer attached to the coffin

- Place a support over the top of the Mummy, secure her and rotate the coffin until she is face down. When the Mummy is removed, a certain amount of stabilisation should be possible to her damaged body, wrappings, and coffin, and this will improve access for museum and academic purposes in future

- Return the Mummy to the coffin on a lightweight support board

- Stabilise areas of detached cartonnage and paint and remove soiling from the coffin lid. The thick deposits currently obscure the painted surface below, interfering with our ability to read the hieroglyphics

Will asked Richard and Helena Jaeschke ACR of R&H Jaeschke to support the treatment. Richard and Helena are two expert conservators with nearly forty years’ experience in the conservation of ancient Egyptian materials.

RESEARCH

Recent hazard awareness courses have mentioned that mummy wrappings or shrouds can contain asbestos. To make sure that we were not exposing anyone to this hazard, Helena Jaeschke carried out further investigations. She reviewed the literature, and contacted Dr Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood at the Textile Research Centre in Leiden. Helena’s inquiries showed that asbestos has never been identified in ancient Egyptian textiles. It is most likely a myth, started to support marketing asbestos as the new wonder material.2

A thick layer of soil covered parts of the coffin lid, obscuring painted decorations, including sections of hieroglyphs that the museum was keen to reveal in order to discover more about the occupant. It was thought that this soil was deposited during a flood, but to confirm this a sample was sent for analysis to Peter Davidson, Senior Curator of Minerals at National Museums Scotland (NMS). He carried out a visual inspection under magnification, which confirmed that it was a river born fine sand or silt sediment.

CONSERVATION TREATMENT

During the first week of treatment the Mummy and coffin were thoroughly documented and the loose debris around the Mummy’s body was removed from the coffin base. She was surrounded by a thick layer of soil, plants and insects, mixed together with fragments of gesso, resin, textile and bone. Will Murray treated the removal of these materials like an archaeological excavation, separating the different constituents into bags for each segment. It soon became apparent that the Mummy’s shroud and decorative linen bands were not wrapped around her body, but only covered her front. Her feet were completely detached.

Richard and Helena Jaeschke ACR joined us at the beginning of the second treatment week. After discussion it was decided to lift the loose shroud, and consolidate the resin on the front bandages with Paraloid B72 in acetone. As far as possible the decorative bands were removed and documented, but the shroud, still attached over the head, was put back in place. By careful manipulation Richard found that the Mummy was not actually attached to the coffin, but was instead stuck down by layers of compacted soil.

To turn the Mummy onto her back, allowing consolidation and repairs to take place to both the Mummy and coffin base, an intricate sandwich was made from Ethafoam blocks, Plastazote, medical cushions used for MRI scans, Tyvek, Corex and ratchet straps. The whole structure was carefully turned over, and the coffin base removed.

The damage to the reverse of the Mummy was more extensive than anticipated. Her back was covered in layers of soil and straw, filling three cavities in the body: the chest, pelvis and lower legs. Removing this material was the next challenge, and there were different perspectives about the degree of cleaning necessary. During the cleaning process most alien material and loose bones were taken out. The decision was made early on to return all human remains to the body, albeit not in their correct anatomical position.

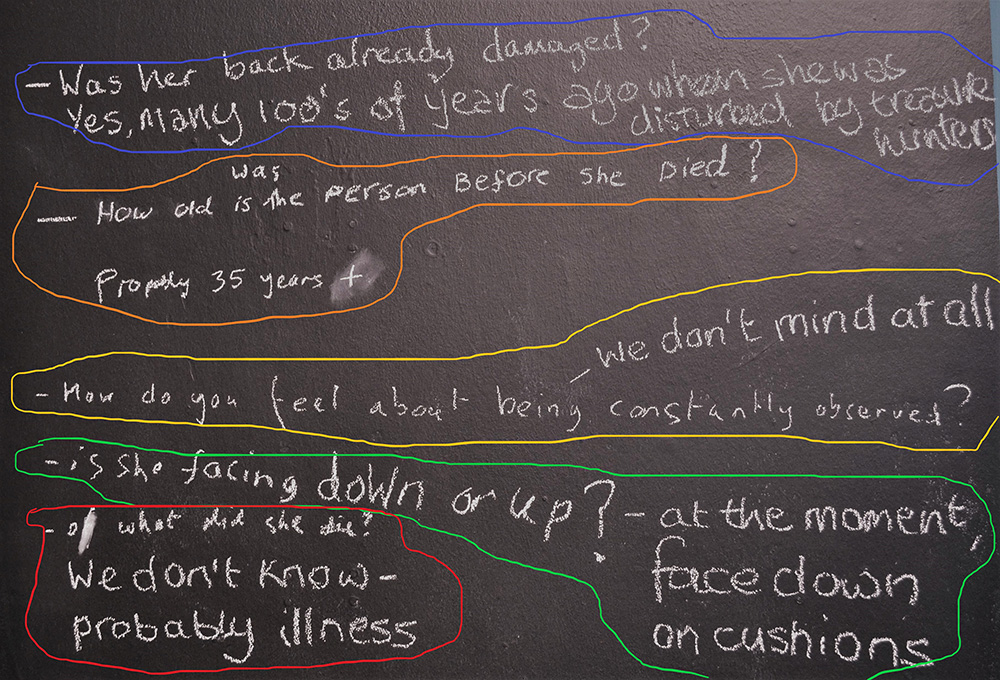

ENGAGEMENT

The most striking aspect of this project is undoubtedly the public engagement element, with conservators working under the watchful eye of museum visitors. One visitor wrote on the exhibition’s blackboard: ‘How do you feel about being constantly observed?’, to which Helena replied: ‘we don’t mind at all’. Working in a team the public aspect soon faded into the background, as we focussed on our work and talked amongst ourselves. A very challenging part of the treatment, turning the coffin over, was carried out on a closed day. This was filmed however, as well as other treatment aspects, and the resulting film is shown in the gallery when there is no conservation activity happening. Thus far, the exhibition has been really well received.

PLANNED STABILISATION TREATMENT

The main priority now is the stabilisation of the Mummy and coffin. The cavities in her body will be packed out in an appropriate manner (methods are currently being discussed and trialled). A support structure will then be created for storage and display, ensuring that the Mummy herself does not need to be handled again.

Gaps in the coffin base will be filled with Paraloid B72 and microballoons, gesso returned wherever possible, and the loose sections of wood reattached. Wherever the cartonnage is stable enough, the coffin lid will be cleaned with 50:50 Acetone and water, in combination with mechanical cleaning. Part of the river soil will be kept in place, because some of the painted areas underneath were found to be very unstable. The loose cartonnage will be consolidated.

NEW DISCOVERIES

Perhaps the most exciting development is the discovery of painted figures on the internal and external bases of the coffin. Both are representations of the Egyptian goddess Amentet or Imentet, known as ‘She of the West’ and linked with the journey to the afterlife. The best preserved of these two paintings is on the interior base of the coffin. It shows Amentet in profile, looking right and wearing her typical red dress. Her arms are slightly outstretched. She stands on a platform, indicating that the depiction is of a holy statue or processional figure. There are at least two other Akhmim coffins known with depictions of Amentet. 3

The fact that the shroud was only loosely covering the front of the Mummy implies that she was rewrapped and reburied, and therefore might not be original to the coffin. Dr Dan Porter from NMS suggested that the soil and straw we found compacted inside the Mummy’s body could be a crude restoration treatment to keep her loose and damaged bones together, and to transport her. The straw and grains still need to be analysed, but they appear to be 19th century rather than ancient.

During the conservation treatment we found many insect exoskeletons in and on all the different constituent materials, including on bones and in the river soil on the coffin lid. These were identified as Smooth Spider Beetle (Gibbium sp.), and Hide Beetle (Dermestes sp.). Gibbium are mostly encountered in warm climates. Larvae feed on woollens, leather and tallow and are sometimes associated with dead animals. Both species have contributed to the instability of Perth Museum’s Mummy.

There is still a large amount of research to be done, but we have made exciting new discoveries, and were able to draw tentative conclusions from these.

About the authors

Anna Zwagerman ACR is Culture Perth and Kinross Conservation Officer

Will Murray ACR is a partner at the Scottish Conservation Studio where he specialises in artefact and preventive conservation www.scottishconservation studio.co.uk

Mark Hall is the Culture Perth and Kinross Collections Officer

Notes

1 McKnight, L. M. and Loynes, R. D., From Egyptian desert to Scottish Highlands – the radiographic study of a twenty-fifth dynasty coffin and Mummy bundle from the Perth Museum and Art Gallery, Scotland, KNH Centre for Biomedical Egyptology, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK, in: Papers on Anthropology XXIII/1, 2014, pp. 108–117

2 The Herald. Newspaper. June 21, 1896

3 Ernest Brummer and the Coffin of Nefer-renepet From Akhmim and Coffin Base with Goddess of the West

Header image: © CPK