Icon’s CEO, Emma Jhita, speaks to Hannah about her journey from conservator to museum director, the link between caring for objects and caring for people, and making a museum more sustainable and relevant.

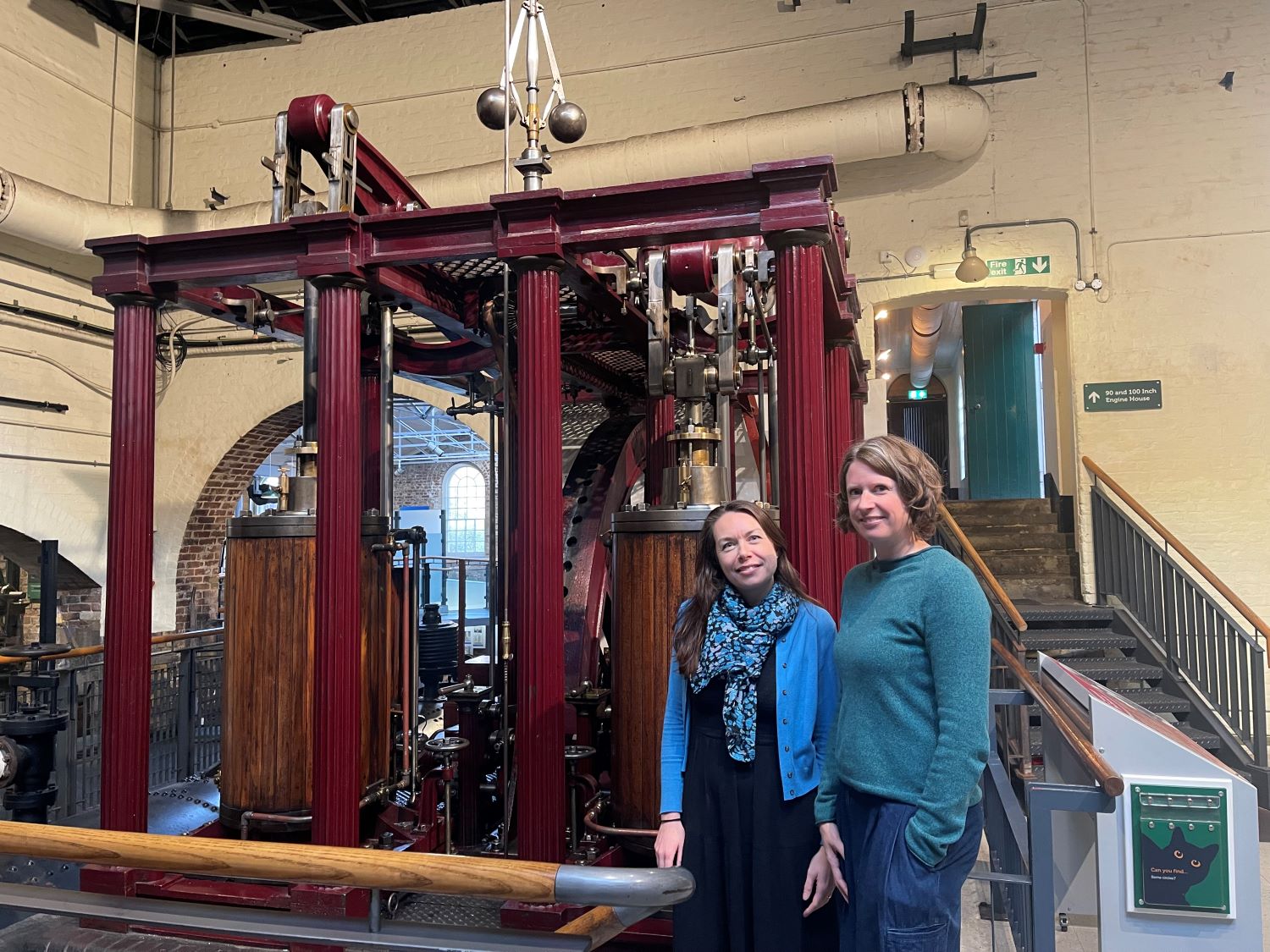

Emma Jhita with Hannah Harte ACR at the London Museum of Water & Steam

Emma: You’ve been Director of the London Museum of Water & Steam (LMWS) for over two years now. What inspired you to transition from Head of Conservation to a museum director role?

Hannah: When I started out in conservation, I didn’t have a major goal in mind for where I would end up. It’s the classic question, ‘Where do you want to be in five years?’ and I always thought, well, a little bit further on, doing something with greater impact.

When opportunities come up, I try to think about where they might lead rather than asking, ‘is this exactly what I want right now?’ I’m a firm believer that it can be the unexpected opportunities that push you to exciting things you never knew you wanted.

I first trained to be an object conservator at UCL and when I finished, three jobs came up. One was in preventive conservation at The National Archives (TNA), which I successfully applied for, and it was brilliant. I had a wonderful seven years doing all sorts of things from pest management to emergency planning. It had a great structure too – really open – and so I got to work with people from across the whole organisation, including the Head of Estates and Facilities when I was just a junior. It felt great, like you could achieve anything.

My career progressed through the British Museum and then to the National Trust. Being Head of Conservation at the Trust had been an early dream, but I realised that even in very senior roles, making meaningful change in an organisation of that size and complexity is incredibly challenging and the broader leadership skills conservators bring can be harder to see.

Even when I did deliver change, the structures and culture of such a large institution sometimes made it difficult for that impact to be recognised. That really mattered to me, and it made me think about finding a role where I could make change happen more readily. And of course, while the possibilities there are enormous, moving things forward in an inclusive, collaborative way can be tough when everyone is already carrying such a heavy workload. Here at LMWS, the role is almost the opposite.

While we don’t have the resources of larger institutions, I can make impact and make it quickly. Currently we are aiming to drive a multi-million-pound project that would create the UK’s first clean-steam heritage operation and reposition the entire site. For an industrial heritage museum of this scale, that will be genuinely transformative if we can achieve it.

Emma: You have worked at some amazing places. The National Archives must have been an absolutely phenomenal first job as a conservator.

Hannah: It really was. It was bonfire night recently and they have the original confession signed by Guy Fawkes. It really does send shivers down your spine. You can see that his hand was shaking when he wrote his signature and you just know what he went through.

And that’s what collections do. There is an understanding that the large and wide-ranging collections within our museums and institutions need to be seen and engaged with. They need to be accessed otherwise they are largely irrelevant, tucked away behind closed doors. Looking at Guy Fawkes’ signature, it’s that visceral connection that you get from seeing something that important in person. That’s what people are looking for.

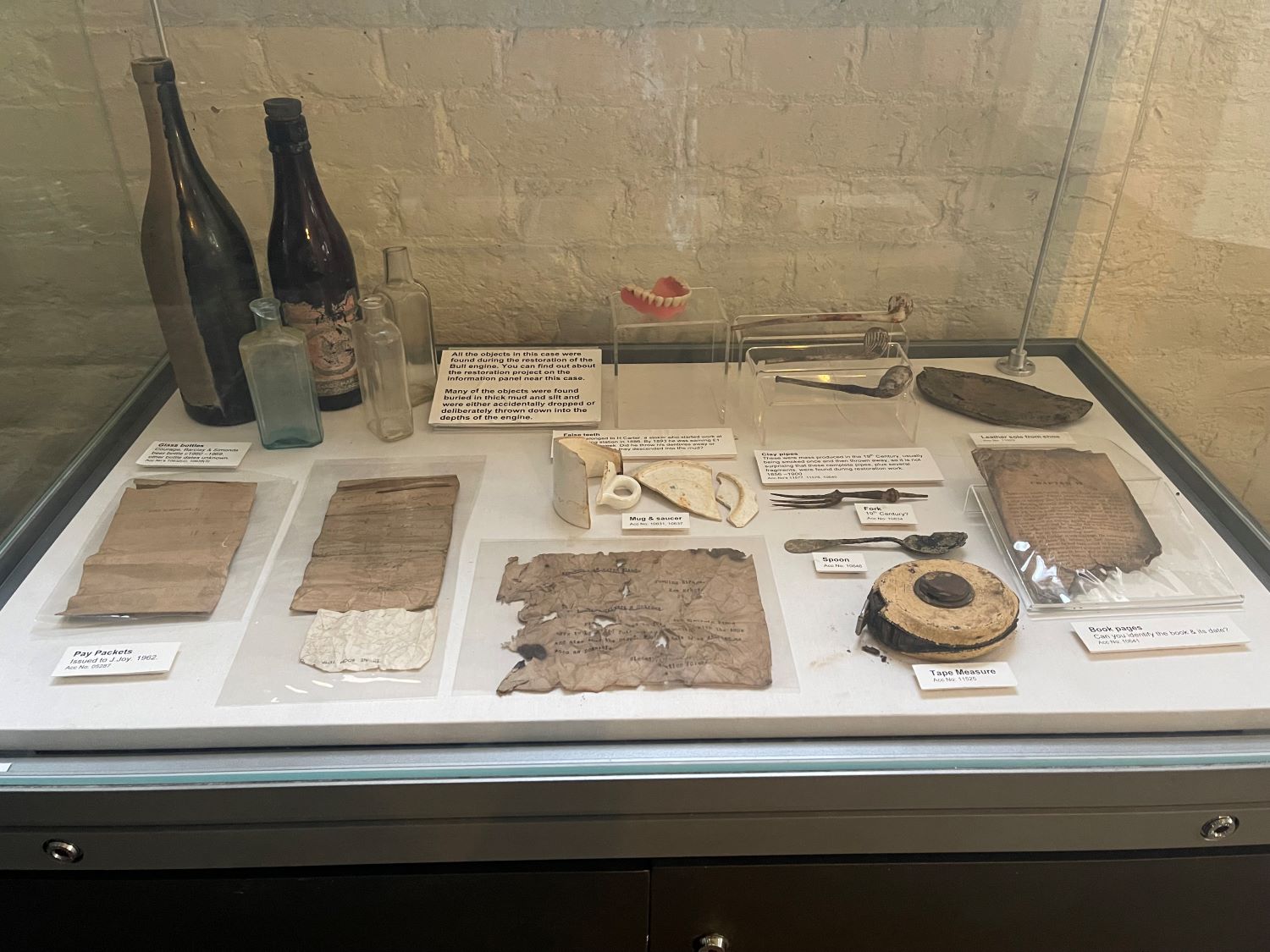

A display of historic objects found in the stomach of the Bull engine during restoration

Esme Ward, who is Director of Manchester Museum, describes museums as places of care. When she says that, she’s referring to everything that museums are doing – it’s not just about caring for objects, it’s about caring for people, how we include them and give them access. Increasingly, that care also extends to the natural world and the planet we all depend on. We do that in a myriad of ways in museums and in conservation, regardless of specialism or whether you are in private practice or work in a public institution. Our work is essentially about people and connection, and the care flows from that.

Emma: That’s a lovely, holistic way of looking at it. The sense that everybody who’s able to engage now – whether they’re volunteers, visitors or part of a school group – they’re all part of the story of the collection and the history. And it’s so much bigger than a conservator or a museum director, or even an entire staff team. So, last weekend LMWS turned 50. How did you celebrate this special anniversary?

Hannah: It was a fantastic day! Our partners Speak Out in Hounslow, a local charity that works with people with learning disabilities and autism, reenacted the museum’s 50 years using a time travelling train, and a choir sang happy birthday in three different languages. Many visitors told us what the museum means to them and how welcome they felt. We even spoke to people involved in founding the museum 50 years ago, and it’s fantastic that they continue to feel excited at the journey the museum is on and where we plan to go next. The engagement and enthusiasm we saw from everyone shows the value of investing in and connecting with people and what this place offers different groups.

Visitors learn about London’s water supply timeline in the Waterworks Gallery

Emma: You’re a fellow of the Clore Leadership programme, renowned for shaping future leaders. What inspired you to join and what made the Clore programme special for you?

Hannah: I wanted to do it because it was a great opportunity – it was prestigious and I wanted to be a part of that. Does that sound awful? I knew exactly what my pitch was going to be, because I felt quite strongly – and still do – that conservation has a much bigger role to play in leadership. At the time, conservators and their skills just weren’t being recognised and I wanted to do something about that. I also felt that to make the sort of decisions that I wanted to make, you needed to be in a senior role. The programme was a stepping stone to do that, so I applied to Clore at the same time that I applied to join the British Museum, and I ended up being offered both opportunities, which was amazing.

Emma: That must have been a very steep learning curve!

Hannah: It was. The British Museum was very supportive, but because I was in a new role it took the Clore placement out of the picture. I thought this was a good compromise at the time but, looking back, I wish I had done one. Placements expose you to the full breadth of the sector and push you outside your comfort zone. But there was still an enormous amount of personal work involved. We had to dig deep and be very vulnerable to build back stronger, and we learned from some incredible sector leaders who shared personal challenges and leadership insights, which was really affecting for all of us.

Emma: Huge credit to you for making that happen and being able to take up both of those opportunities.

Hannah: It was absolutely terrifying but amazing at the same time! And an absolute game changer.

Emma: Moving on to Icon’s recent ACR Conference where you hosted an inspirational panel around conservators as leaders and change makers, is there anything in the heritage sector that you’d like to see change to support that?

Hannah: I’m enjoying the change we’re seeing at the moment, with conservators being better recognised for their expertise. Part of that is down to the fact that there are fewer training routes now so the talent pipeline is smaller, but it’s resulting in higher salaries than previously. So, things like being included in the Museum Association’s salary recommendations and having our own category within that is good, because conservation is sometimes pigeonholed as a detail-focused profession and people don’t always see how we fit into the bigger picture.

I think there is some PR work we need to do around this which wouldn’t require a lot of change, as we are already involved in projects most of the time. It’s just whether other people know we are. And I guess it’s about educating the rest of the sector that actually, this profession is much bigger and can contribute far more to organisational leadership and change than people often realise.

Emma: I spotted a quote on your website about ‘the power of culture and heritage to change lives for the better’. We’ve touched on this already, but I’d love to hear more about the role of LMWS and how its collection is achieving this.

Hannah: Doctors are now prescribing visits to museums to improve health by engaging with culture and the arts. As a museum, we obviously have a role to play in that. But I think for LMWS, and the reason I took this job rather than anywhere else, is because the potential to change lives for the better here is enormous. If you take industrial heritage and engineering, there’s a lot of discussion about the loss of skills in this area and what we need to do to address this. We made it our business to consider how we could engage young people which resulted in our STEAM Explorers programme. Feedback we’re getting is that the young people involved are finding the school system quite challenging. Theory is important, but they want more hands-on, problem-solving activities that result in something tangible.

Museums really do change lives – we can help to close skills gaps and spark the kind of interest that enables young people to find their place in the world. But also, this is a water pumping station. It was born out of trying to solve the Great Stink of 1858, when water-borne diseases like cholera and typhoid were killing large numbers of London’s population. The engineering done here didn’t just solve a local crisis – it fundamentally changed how cities across the world understood public health, water and sanitation.

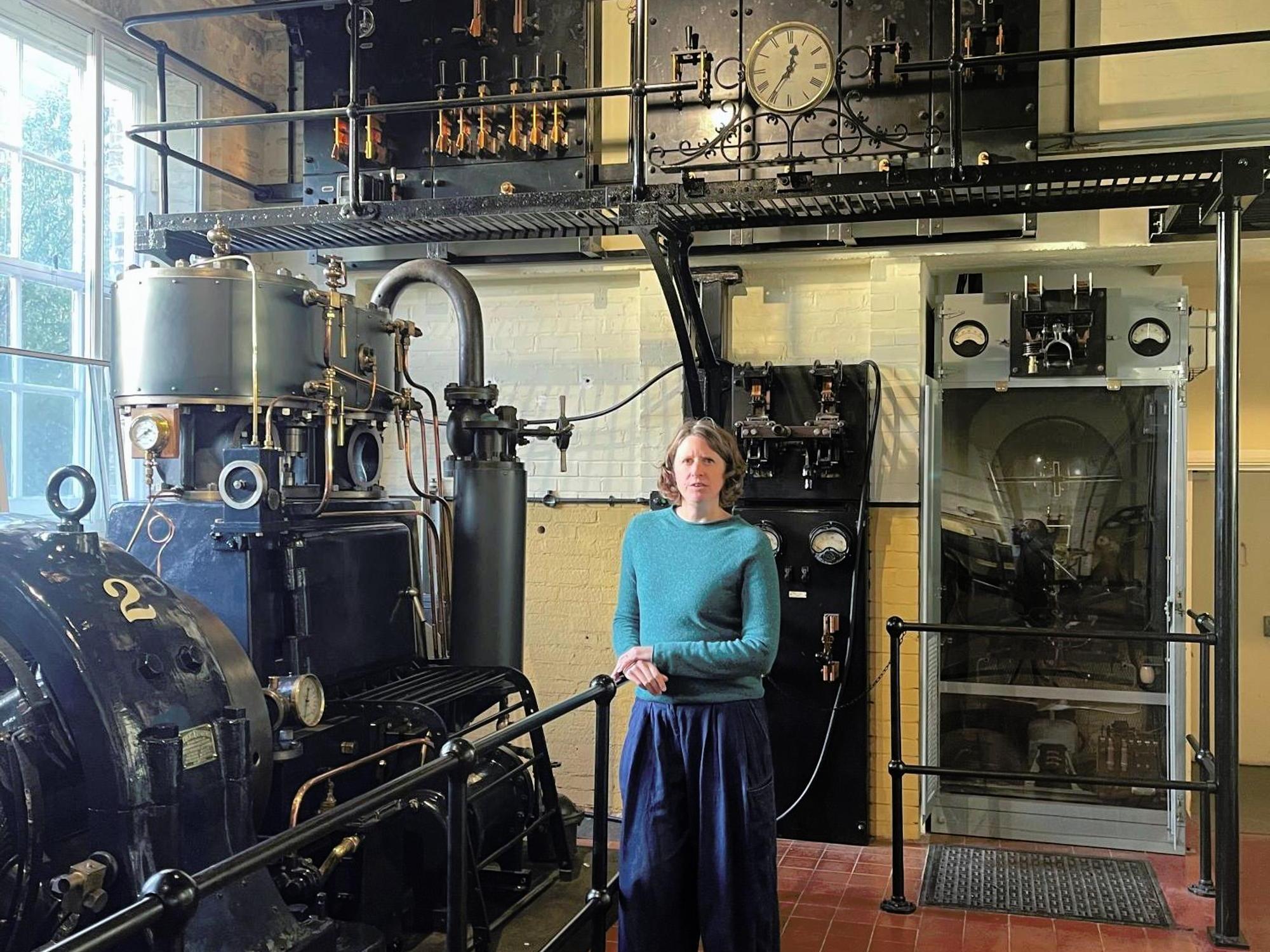

Oiling the triple expansion engine

Arguably, we’re facing equally urgent challenges today when we think about our watercourses in the UK, global water shortages, fair access to clean water and the general sustainability of the planet’s blue resources. At LMWS, we are very much looking to the future and how we can advocate for change and help people connect with the groundbreaking innovation and problem-solving that originally happened on this site. This place has always been about saving lives through engineering, and it still can be.

There are opportunities for these engines and this site to have a much bigger voice, a much wider reach and a much greater impact. I want to be the person to realise that.

Emma: That’s phenomenal in terms of going back into history, making that tangible connection and bringing it forward hundreds of years to demonstrate its relevance now and into the future.

Hannah: They’re not just old machines. At the time, they were the answer to a massive problem, and there’s something really inspiring about that kind of engineering mindset – it shows that a positive future is possible.

As a conservator, the challenge for me is that these engines are dynamic heritage. They’re designed to move, and to really understand them – and to connect with the innovation they represent – people need to see them in action. That makes them very different from a standard museum object and it means they can play an even bigger role in engaging people than if they were to remain static.

Emma: You’re in a fairly unique position in that you’ve got the training and expertise of a conservator, and you’re also leading a museum. It must be helpful to bring all that knowledge together?

Hannah: It was a fairly big jump I suppose, but I’d worked in lots of different contexts – in archives, in museums with huge collections, and then at the National Trust, with Grade I listed buildings. That range of experience has really helped.

If we look at the Great Engine House at LMWS – in itself, it’s a brilliant conservation project and the work is much needed. When you look up at the building from the car park, you can see the cornicing along the top is failing. The window frames are all iron and as they corrode, they’re crushing the panes of glass. Is it going to change the museum story on its own? No. Is it going to bring any kind of fundamental change to the way the museum operates? No. But it is essential. So, in the master plan I’m developing, the Great Engine House is piece number one – secure the heritage that you’ve got.

The Great Engine House

The next stage is to think about the site, how it operates and stepping into a more sustainable future. We’re in conversations with the National Lottery Heritage Fund about how we can bring that to life. Our Steaming into Sustainability project explored pathways for steaming a dynamic industrial heritage collection sustainably and we believe we have identified an exciting way forward using hydrogen. At the same time, I want to shift the site 90 degrees so the entrance is on the main road, helping us interpret the site properly as a water pumping station and a place focused on the sustainability of blue resources. I think that it is the next step for our living museum.

The Electric House at LMWS

Luckily, I have a brilliant team, who consistently go above and beyond, and they’re already embracing these goals and thinking about every opportunity to maximise our relevance. Our volunteers, members and visitors are on board with that as well. It’s a bold and ambitious direction, and there is risk in that, but if we get there, we’ll be much more secure and impactful as a museum.

Emma: Hannah, congratulations on everything you’ve achieved so far and thank you so much. It’s been really enlightening!

To learn more about London Museum of Water & Steam, please visit their website at www.waterandsteam.org.uk.