Bought for Lady Londonderry's first home and said to have belonged to Queen Mary II, the 18th century Genoa bed had several interventions during its lifetime. Claire Magill ACR recounts its treatment during a three year project to restore the West Wing Rooms at Mount Stewart.

Introduction

Between 2012 and 2015, Mount Stewart, near Newtownwards, Northern Ireland, underwent a three-year, £8 million building project: Mount Stewart Renaissance. The project saw the house restored to its jewel-like condition of the early twentieth century, when the wife of the seventh Marquess, Edith, Lady Londonderry, and their family used the property as their favoured retreat. The project included structural repairs to the house, improvements to services and also careful conservation and restoration of its treasures.

Throughout the project, the team were keen to ensure that the work benefitted visitors, the local community and the economy.

New jobs were created, local companies were appointed and there were opportunities to learn and share new skills from specialists brought in from across the National Trust. Wherever possible, visitors were given physical and intellectual access as the work progressed, so that they could feel involved in both the detail and the sheer scale of the restoration of this local landmark, including an accessible Collections Store, a Conservation Studio and a six-part television series The Big House Reborn.

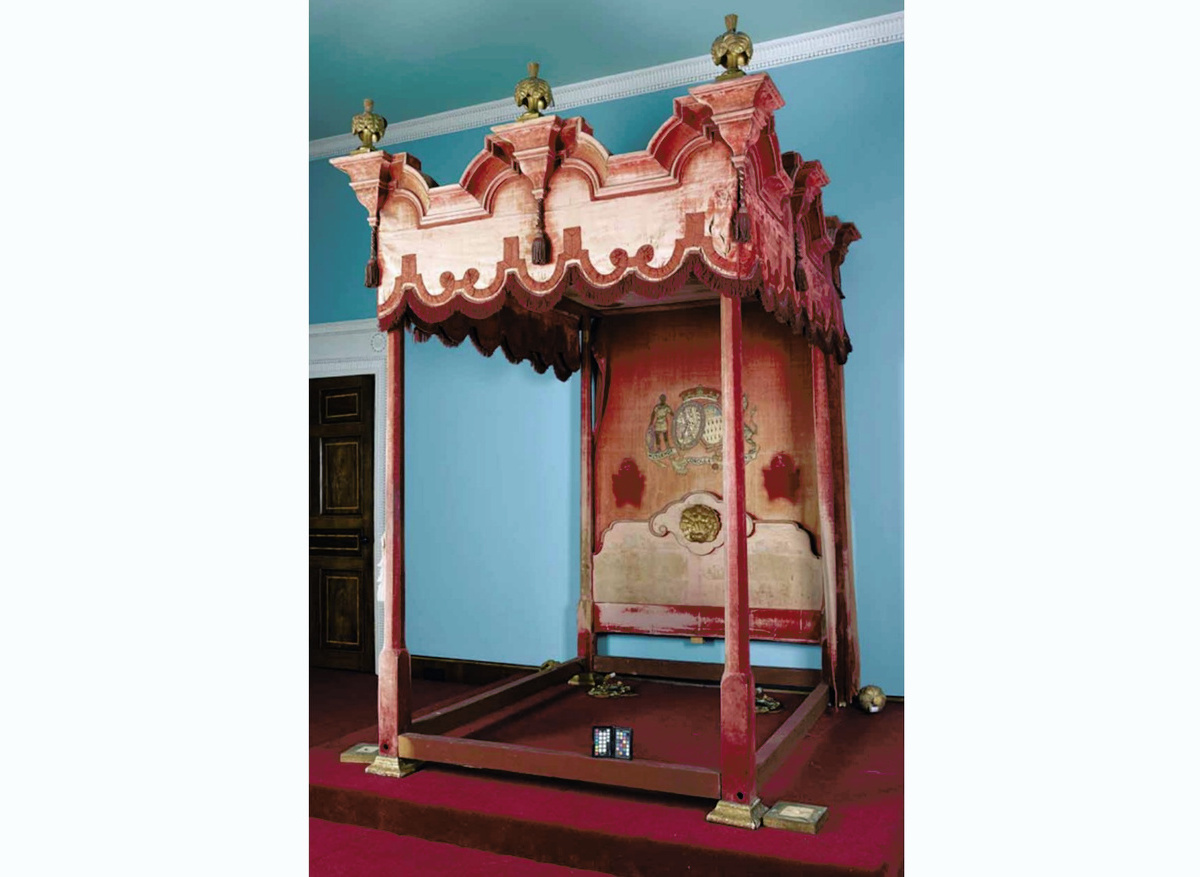

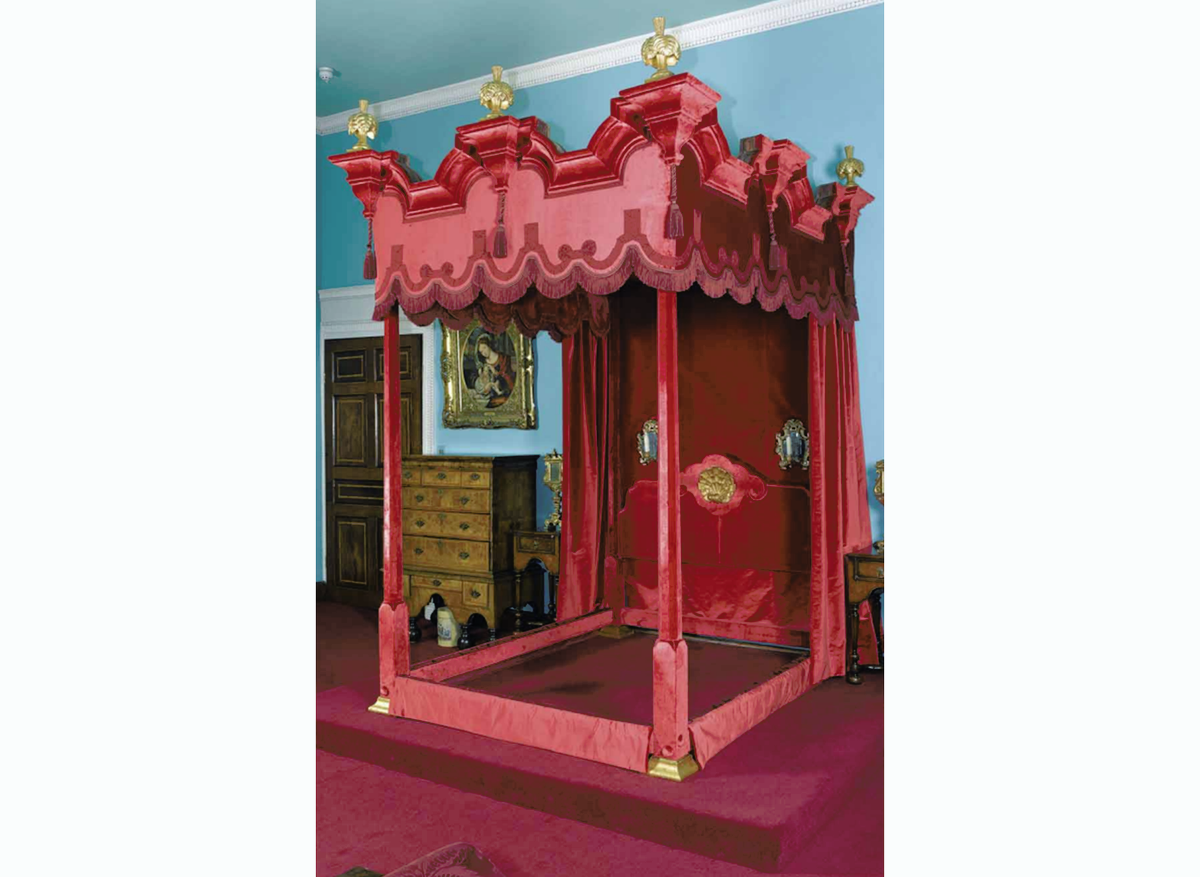

During the main project, we shared with visitors the extent of the outstanding work. This resulted in a generous gift from a private foundation, which supported an additional conservation project in the West Wing and enabled us to open its rooms to the public for the first time. Part of this work involved the conservation of the four poster bed in a bedroom named ‘Genoa’, a project that spanned three years from the initial research and gathering of samples to final completion. Much of the bed was in such poor condition that, unusually for a conservation project, various elements were conserved but then retired and replicated. Using sumptuous textiles and trimmings, we have reproduced those elements to reflect the vibrancy and theatrical approach so typical of Edith Londonderry’s tastes.

Objectives

The project entailed restoring the furniture and textile elements of the Wing’s private rooms. The teams of specialists who had worked on the main building project understood the concept of ‘spirit of place’ that informed all the interventions at Mount Stewart, but the West Wing project provided the opportunity to realise this approach in a very different way. As well as conserving the tangible heritage as far as possible by stabilising the textiles, the aim was also to conserve Mount Stewart’s intangible values by reinstating Lady Edith’s original vision for rooms which now looked tired, shredded and sad.

Whilst the principle of conserving as much as possible guided our decision-making, it was balanced against an ambition for the textiles to regain their colourful and dramatic appearance as in Lady Londonderry’s time. Elements which would not convey these values after conservation were therefore retired. Albeit potentially controversial, this approach was essential to ensuring that the rooms reflected Mount Stewart’s ‘spirit of place’.

Informed by a ‘statement of significance’ written by the curator, specifications were drawn up, in collaboration with the Trust’s conservation advisors, for the conservation of original textile elements, the making of replacement textile elements and furniture conservation.

The work involved in conserving and restoring objects and interiors, and opening the rooms to the public, was designed so that staff and visitors would understand their significance better, illuminating how the rooms were originally intended to be viewed and used and giving greater insight into the vision and personality of Lady Edith.

Engaging the public was also a way to promote understanding, enjoyment and participation in the Trust’s core purposes, and to develop the skills and experience of both National Trust Conservation teams and external conservation specialists. The outcomes of the work were intended to improve the visitors’ experience through enhanced interpretation. In sum, this project aimed to let the spirit of Mount Stewart shine and speak for itself.

Background

Edith, Lady Londonderry, chose the West Wing for her bedroom and private apartment as it was the most secluded part of the mansion, with the best views of Strangford Lough and the Mourne Mountains beyond, as well as of her gardens. She loved light and the large windows in the West Wing rooms provided the context for the textiles and furnishings in these spaces.

The 18th century bed had had several interventions during its lifetime. It was said to have belonged to Queen Mary II and was bought for Lady Londonderry’s first home, Springfield in Rutland. Parts of the bed probably date to c1700s, and the velvets and trimmings used to cover the bedstock were certainly added later. Edith adorned the hangings still further with a large applique coat of arms on the head cloth and crests of the Women’s Legion on the inner valance.

This inner valance was in good condition and therefore the decision was taken to conserve it and use it as the point of reference for the final appearance of the bed, taking our lead from it when choosing new velvets to replace textiles that had deteriorated beyond economic repair. Replacing the red velvet re-injected colour and vibrancy into this room, and reflected the spirit of Mount Stewart as well as of Edith herself, whose approach was to replace rather than allow her furnishings to fall into poor condition.

The Work

Each element of the bed was inventoried on the Trust’s electronic Collections Management System (CMS) and its condition checked by textile and furniture conservators. On the basis of the specifications four suppliers were appointed (furniture conservator, textile conservator, interior designer and seamstress) whose teams helped dismantle and pack the various elements into packing cases for transport to the contractors’ workshops. Packing and transport was in itself a complex procedure because of the large number of elements and their fragility, whilst getting them to the right place at the right time involved a lot of communication and organisation.

The inner valance, which we wished to conserve, turned out to be attached in a complex fashion, a fact which only became evident during dismantling. Therefore the decision was taken to leave it in place and for the textile conservators to travel tothe property to carry out their work in situ.

The original plan for the coat of arms on the headcloth was to conserve and reinstate it. However, the specification for the work elicited the response that conservation treatment would extend the embroidery’s life for only forty to fifty-five years, and that it would still appear lacklustre in comparison to the new elements (velvet, trimmings and passementerie) and the desired vision for the bed. Therefore the project team decided to conserve the coat of arms and archive it. A textile conservator who was also a trained needle-worker was commissioned to drew up templates and recreate the coat of arms. This took eight months of intense work.

Staff, volunteers and supporters were kept abreast of progress by regular updates of blogs and Facebook pages. Groups of staff and volunteers were given regular access to the work, rather than inviting them only to a ‘big reveal’ upon completion. As a result, these stakeholders understood the reasons behind the decisions that were taken, securing their support for the bold approach to the bed. The donor family were engaged in the same way, making decisions collaboratively, for example over the colour and quality of the replacement silk velvet. Working closely with our stakeholders in this way meant that they waved the flag for the project, which had a great positive impact on the visitor experience.

The conservation studio set up in the house as a legacy result of the building project enabled staff and volunteers to remove and clean original elements on site under supervision. Not only were their skills and experience developed, but also visitors could benefit by seeing the work taking place.

A celebratory booklet of ‘before’ and ‘after’ images of the bed was created for the foundation that donated the funding, helping them to understand the impact of their gift. On completion of the project, a final book was created covering all of the work of the project, which is currently being printed as a souvenir to enable visitors to appreciate the extent of the work, as they enjoy a guided tour of the spaces for the first time. The book continues to generate support for the project and the work of the National Trust and, with copies sent to each of the main contractors, it has also helped to share the details of the project beyond Northern Ireland and beyond the National Trust.

A page of the book created to celebrate the project, showing images of the Genoa Bed before treatment

Budget and Timescales

The complete budget for the three year project to open the West Wing rooms was £300,000 ($450,000), of which the conservation and restoration of the Genoa bed cost £72,000. The treatment of four historic beds, and over fifty-five items of furniture (sofas, wingback chairs, bidets) and textiles (curtains, pelmets, dressing table skirts, altar cloths) was also funded (thanks to beneficial exchange rates). Moreover, clear and detailed specifications and the guidance of specialist conservation advisers facilitated work with local suppliers from the building project. These two factors allowed us to commission over 35% more work than originally anticipated.

The funding did not cover associated interpretation, which in hindsight it would have been beneficial to include, although this is not always within the interest of particular funding bodies. However, alternative arrangements can be planned for work that is not aligned with donors’ interests.

Partners

The resident donor family were very closely involved. Lady Rose Lauritzen lives at Mount Stewart for six months of the year, and she was invaluable in decision-making through her link to the past and clear memories of her grandmother Edith, Lady Londonderry, and of how things were run at Mount Stewart.

Many external suppliers were also involved. As several of the rooms are still used by the donor family, the specifications needed to accommodate this use – whether the room will be open to the public every day or only a few times a year, whether the bed will be slept in or the furniture sat on and so on - in order to make appropriate decisions that balance conservation and apply restoration techniques with conservation principles. Crucial to achieving this outcome was collaboration with accredited conservators who were able to apply their professional judgement to this particular context. Indeed one of contractors used the project for their successful Professional Accreditation application.

Outcomes

The response from the funders and from our supporters has been overwhelmingly positive. Through careful interpretation, our supporters have been able to understand Edith, Lady Londonderry and the spirit of place that is preserved and now reanimates her home. Interpreting this rationale has helped an understanding of why some elements have been retired and some conserved and to reflect the theatrical and joyous approach to textiles throughout the interior.

This spirit is also reflected outside the house where Lady Edith’s exotic avant-garde approach to planting has been recreated in the gardens, showing the same confidence in putting bold and riotous colours together as inside the house, and resulting in Mount Stewart’s consistency of setting both inside and out. Visitor feedback witnesses to how much they love the results, and the fact that they are returning to see different rooms opened at various times of the year, in line with how the room is used by the family.

Lessons Learned

The ‘statement of significance’ proved invaluable, helping with the specification of the work and the commissioning of external specialists by articulating the objective of the treatment, and providing the rationale underlying the decisions to conserve and reuse or recreate. Many decisions arise during the life of a project and a clear vision that can be readily shared makes taking those decisions more straightforward by providing clarity of thought and consistency.

The opportunity to undertake this project arose in the final year of delivery of the main building project. This meant that resources, in terms of capacity and energy, were at their lowest. The wisest move was not only to build the predicted resource needs into the business case, but also to add a healthy contingency to cater for the ‘unknown unknowns’.

Engaging with stakeholders was essential to bring them along with the decision-making. As project manager, I prioritized making myself available, through attending open mornings, conducting briefings at volunteer meetings at the start of the open seasons, being available for informal discussion and ad hoc walk-abouts as well as scheduled days on site. Bringing people along with the work meant that more was achieved than the sum of its individual parts, in the emotional as well as the technical and intellectual impacts of the project.