In 1540, it was Henry VIII who gazed up at the rotating sun, moon and ornate signs of the zodiac on his astonishing and newly installed Astronomical Clock located at the heart of Hampton Court Palace (Figure 1). Almost 500 years later, in August 2007 we too turned our gaze upwards to watch its dials and gearing being lowered down to the courtyard’s covered colonnade (Figure 2). The project to conserve Hampton Court’s Anne Boleyn Gatehouse and Henry VIII’s great Astronomical Clock, funded by conservation charity Historic Royal Palaces, was underway.

Introduction

Our brief was to commission the conservation treatment of the clock, a complex instrument essentially comprising three metal discs and a gearing mechanism. For this, conservators, curators, paint and metal specialists and horologists were brought together ready to embark on the examinations and investigations that are the prerequisite to debating and deciding a treatment specification. We needed to know the condition of the clock, the extent of original and restoration material, and the treatment methods that could successfully conserve decorative paint surfaces in an outdoor environment. Metaphorically speaking the clock was ticking for all this had to be accomplished by April 2008.

Figure 1. The Anne Boleyn Gatehouse, Hampton Court Palace before building conservation work. The clock sits 15 metres from ground level.

What the Archival Records Revealed

Figure 2. The dials and gearing on display under the Colonnade in Clock Court.

Henry’s VIII’s clock is deemed to be a marvel of Tudor engineering and one of the pièces de résistance of his ambitious quarter-century renovation of Hampton Court Palace. Its mathematically complex gearing runs each of the three dials (lunar, solar and sidereal) at different rates in order to show the passage of the sun, moon and stars with the earth at the centre of the universe. Commissioning this work is a testimony to Henry’s learning and patronage of men of science. It is thought to have been designed by ‘the devisor of the King’s horloges’, a Bavarian astronomer named Nicolaus Kratzer, and constructed by a French clock-maker, Nicholas Oursian, whose initials are incised into the gearing (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Horologists Jonathan Betts and Peter Linstead-Smith examine the gearing with Zoe Roberts. Nicholas Oursian’s initials can clearly be seen.

As well as being a scientific instrument of note, the astronomical clock was also a work of art; its three decorative dials were further embellished within a painted frame. In the reign of Elizabeth I the dials were clearly described:

"Three plates of the dial in the paved Court with the twelve signs [of the zodiac] in the outermost plate and the two lesser plates with ... figures of the son and age of the moon...

for painting and gilding the rest of the outermost concave which describes the four parts of the world with ships sailing ... representing also the buildings on land with hills and dales ...

for painting and colouring with white and black the outermost crest and in it four badges with gold and blue – i.e. the arms of France, the Rose and Portcullis with H and R [for Henry Rex]

Regrettably, neither the painting on the ‘concave’ surround nor Henry VIII’s decorative scheme survive. The picture sketched by archive references was one of repeat restorations and repairs over 500 years, one important impetus for which was accurate time keeping. Both orthographically and stylistically it was evident that the earlier Tudor scheme had been superseded. The documentation backed this up, suggesting the current scheme to be a 1960 replication of an extensive Victorian restoration. In the 1880s, the Croydon-based clockmakers Gillett and Bland constructed a new movement and re-painted its dials as part of a major works programme to renovate the palace.

Our Challenge

Many years on, exposed to rain, wind and sunlight, the 1960 re-painted scheme, although still beautifully detailed, had chalked and faded and was flaking (Figure 4). The most significant alteration occurred in the areas of red and blue paint. Inevitably like those before us, we were now faced with the critical need to save another of the clock’s long line of decorative schemes.

Figure 4. Detail of the condition of the painted surface on the sidereal dial before treatment. The green areas are where the undercoat is showing through.

We turned our efforts to the archaeological and technical analysis of the clock’s decorative layers. The gearing and its working order were the remit of the Cumbria Clock Company.

Materials Analysis

First we searched for original Tudor materials. Cross-section paint analysis backed up the findings of the archival research. All paint on the face of the dials had been comprehensively stripped away in 1960. FTIR analysis informed us that most of the 1960 work was done with an alkyd-based paint. Its red pigment was an exceptionally unstable synthetic organic pigment (possibly toluidene red) which explained its dramatic fading. Tenaciously we probed further, hoping for traces of earlier material. Our paint analysis specialist’s persistence paid off when forensic-scale evidence of azurite was found on two of the dials. Not only did this help to date parts of the clock it was physical testimony of the Tudors’ colourful palette.

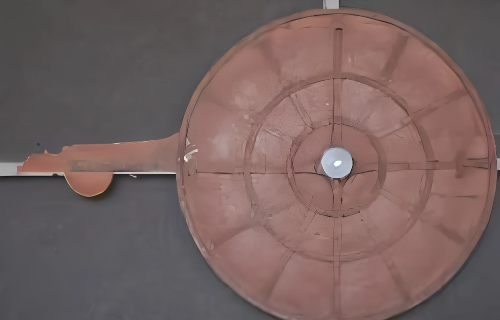

In terms of substrate, the dials were fabricated from sheet copper, approximately 5mm thick, which XRF analysis revealed was dipped in a lead-tin alloy. Each dial was made up of irregular sized sheets of metal. The largest dial – about 2.5m in diameter – is composed of sixteen pieces. Each copper disc was riveted then later strap-attached to a wrought-iron armature (Figure 5).

Figure 5. The reverse side of the solar dial showing the iron armature and corroded pointer support.

Treatment Decisions

Specialists in metals conservation advised that the dials were generally structurally stable. Only a new support was required to the pointer of the solar dial. It had been weakened by corrosion and appeared to be a 1960 replacement along with the pointer itself.

The most challenging treatment decision pertained to the painted decorative scheme. Three differing approaches presented themselves:

- Replication to completely strip and repaint the dials, similar to the 1960 approach and those prior. This standard artisan practice achieves the clean surface necessary to ensure best possibly adhesion of paint to substrate. Our question was whether or not the 1960 paint should be saved as part of the history of the object.

- Conservation to preserve the existing scheme by consolidating and isolating the deteriorated paint surface and in-painting areas of loss. The questions here were: would conservation-grade materials and methods survive the external environment; would the final appearance be aesthetically coherent with that of the restored gatehouse?

- A compromise position that would retain as much of the existing scheme as possible whilst also attaining durability. (The dials are positioned 15 metres above ground making frequent ‘refreshment’ painting difficult). Some of the questions here included: could adhesion to the existing paint layer be achieved; was a compromise treatment viable in an external environment; how much material could be preserved?

Our specialists agreed that the clock faces remained very legible despite significant change in the red and blue paint, erosion of black shadow lines and numerals and some loss of gilded detail. Overall, the 1960 scheme had been well executed and much detail was still visible in the astronomical characters (Figure 6). Moreover, archival research and paint analysis had not yielded sufficient evidence of pre-1960 materials and design on which to replace the current scheme.

Figure 6. A detail of Pisces on the Sidereal dial.

The compromise approach was therefore chosen. This would retain and reinvigorate the present decorative scheme, in particular its finely painted and detailed figures. Areas of colour that had irretrievably faded would be overpainted. The worn gilded symbols and astrological figures would be patched where necessary and retouched for heightened definition. This treatment would allowed us to maintain all physical evidence provided by the clock dials while recreating their vivid appearance as restored in 1960 and likely to be in closer accord with the Tudor character.

However, this approach did pose the long term risk of adhesion failure between the old paint and the new.

Treatment Methods and Materials

Historic Royal Palaces conservators worked closely with Hare and Humphrey’s, the selected conservation workshop, to devise the treatment specification. To give our chosen approach the best possible chance of survival we thought very carefully about our use of materials and methods. Below are some of the important considerations that informed our discussions and shaped the final treatment:

Keeping the palette of treatment materials simple

By minimizing the addition of new materials we hoped to decrease the risk of technical failure that can be triggered either by mixing incompatible materials or by the number of interfaces created.

For these reasons, it was decided not to use the conventional conservation approach of a barrier layer between the 1960 paint and the new paint. The 1960 decorative scheme has been very well documented, as has the 2008 treatment. All layers will clearly be visible in cross-section. For the same reason we decided not to consolidate loose or flaking paint and gilding but to take it back to a sound edge and use a primer (Figure 7).

Figure 7. A detail of Leo after cleaning. Areas of loss have been taken back to sound edges and primed ready for patch gilding.

To preserve as much of what was sound of the 1960 scheme as possible

It was clear from early cleaning trials that the faded 1960 red paint needed to be overpainted. However, we ideally wanted to keep the overpainting as minimal as possible. At first we aimed to just clean and re-saturate the blue with a clear resin. In practice this was not possible. Although enzyme cleaning removed the chalky surface successfully, over larger areas the paint was too worn and patchy (Figures 8&9). We therefore had to proceed and overpaint the blue as well. The minimal approach worked most successfully for the solar dial where the black paint and gilding survived in excellent condition. Approximately 95% of this dial’s decoration remains the same as at the beginning of the project.

Choice of paint system

The selection of a paint system was difficult and wide consultation revealed no consensus of opinion. Discussions centred on durability, reversibility, compatibility and its properties on ageing.

Examples of different options included: the use of an epoxy-based paint, which would give the most long lasting finish but could only be removed in a way that would also destroy material evidence. Another possibility was a modern alkyd-based paint with acrylic component for increased flexibility, recommended as the most durable in the industry in external application. However, this type of paint contains pigments not comparable in quality to those found in artists’ paints and therefore much more likely to fade within a decade.

We were faced with many choices but no perfect solution. In the end we opted for Hare and Humphrey’s recommendation. Their preference was for a lead-based oil paint. Based on their practical experience, it keyed well to all surfaces (a necessary requirement when being applied on top of the 1960 alkyd), had excellent durability and should degrade in a more sympathetic manner than a modern paint system. In order to enhance the longevity of the colours and to get an exact match to the 1960 palette, light-fast, modern pigments were added. Working on an object from a Scheduled Monument allowed them to make this choice and obtain the appropriate dispensation for use of lead paint.

The finishing touches

Overall, we needed to ensure that all new paint, retouching and patch gilding harmonised with untreated areas. It was crucial that a balance was achieved across each dial and between all dials. There was close collaboration between HRP staff and Hare and Humphrey’s, including workshop visits. In order that the correct balance was struck for the retouching of areas such as the astrological figures, alongside scrutiny of physical evidence, photographs of the 1960 dials were consulted. A breakthrough came when the 2/3rd size replica of the Tudor dial, commissioned in 1962 for the Science Museum’s new Atrium, was unearthed at their Wroughton store. It was painted by the same firm of sign writers that carried out the 1960 work on the original clock dials. Although more crudely styled, it was to be an invaluable source for comparing the three dimensional design and shading of the figures before weathering.

Conclusions

The research, investigation and treatment of Henry VIII’s astronomical clock dials proved both exhilarating and daunting. Despite the project’s limited timeframe we were able to study and record the dials more thoroughly than at any time in their history.

The suitability of conservation techniques and materials for treating outdoor painted surfaces was the issue that came to the fore in this project. Technical information was not always easy to access and there was much conflicting advice. There are many new proprietary products on the market and it was difficult to judge the appropriateness of these modern materials recommended to us – the timescale of the project precluded material testing trials prior to treatment. As conservators we are perhaps conservative in our choices of materials, symptomatic of bad experiences of the past and the limited research on applications of new materials being carried out in and for our field. Within this context, initiatives such as that recently launched by Rohm and Haas are of great importance.

The dials were reinstated at the end of April 2008 (Figure 10) and as part of the restored Gatehouse will form a centre piece for Hampton Court Palaces’ celebration of the 500th anniversary of King Henry VIII’s accession to the throne in 2009. Aesthetically, they achieve an appropriate balance between new and old both for the building and the object. Monitoring and data collection of the decorative surface in the years to come will enable us to evaluate our approach but ultimately only time will tell how successful our choices have been!

Figure 10. As work nears completion on the Anne Boleyn Gatehouse the restored cupola and clock are revealed – May 2008.