Often but inaccurately called Big Ben, the clock and its tower at the north end of the Palace of Westminster, now called Elizabeth Tower, is a world-famous landmark which has recently undergone major conservation works. Alexandra Miller tells Icon News about Cliveden Conservation’s part in this huge project, returning the iconic clockfaces and surrounds to the original 1850s Charles Barry colour scheme.

The well-known image of the stone clock face surrounds prior to works commencing

This must have been an enormous task as well as an incredibly complex project to manage. Tell us about the planning and logistics challenges.

The Restoration of Elizabeth Tower was a hotly anticipated and highly sought after tender, with the famous stone clockface surrounds being probably the most prized part. Due to the lack of external access and their lofty positioning forty-five metres up the tower, the extent of the works needed was largely unknown. We based the original scope of works on the ‘classic’ stages of any major decorative restoration:

- Carry out investigations into the historic paint schemes and, using the findings, agree the correct scheme to be reinstated.

- Remove any failing or delaminating paint layers, paying extra attention to the gilded areas as gold leaf is particularly sensitive to decomposition - or more precisely its bonding coats.

- Reinstate decorative scheme - it was first suggested that the scheme may be the 1858 blue/green and gold scheme as previously proposed in the 1980s.

It was ultimately decided, based on material and archival evidence, to reinstate the scheme detailed in the 1853 Charles Barry watercolour: clean bare stone with blue and gilded highlights. Following this, we had a clear understanding of what the final scheme would look like and developed the scope accordingly.

The whole project included works to the entire building in some form, inside and out. This colossal undertaking called upon the expertise of a wide variety of trades and industries and works hit the ground running from the start. The clock faces were no exception; once access was granted, it was all hands on deck - us, stone masons, glaziers, metal workers and industrial decorators. Like a jigsaw, we all needed to slot into each other’s programmes seamlessly to keep this well-oiled machine ticking along.

Our works were arguably one of the most complex and changeable, most debated and, at least aesthetically, the most anticipated of the whole project. The complexity was in part down to the fact that our scope of works was being written in real time as we progressed. With so many unknowns, rigid specification would simply not have worked.

We foresaw this by putting together a multi-disciplinary team of conservators, decorators, gilders and skilled labourers to cover as wide a skillset as possible. Due to the high security protocols in place, each team member needed to be security vetted months ahead of the project commencing. The brilliant and adroit Cliveden Conservation team adapted and skill-shared as needed, creating a level of efficiency and cooperation that ensured the project was a success.

What made this project stand out from other large and complex high profile projects was the logistics of the vertical work area, across all of our works packages (which included internally the partial colour analysis and the full reinstallation of interior decorative schemes and externally the works discussed in this article}. External clockface works were particularly challenging to manage because of how the scaffolding sealed off from view the majority of the clockface, with gangways no more than two metres wide (barely 60cm in some areas), meaning that the clockface surrounds were only visible in two metre high horizontal strips.

Excellent communication and attention to detail, especially around the areas obscured by scaffold boards, were essential to ensure when paint stripping that no tide lines were left or decoration missed. The completed clockfaces were only seen by us for the first time once the scaffold was struck - the same time as everyone else saw them!

Tell us more about the extensive analysis which was carried out to determine the original intended colour scheme of the famous clock faces.

First, we had to carry out the historic paint research - paint chips were extracted, their locations meticulously documented and then sent for microstratigraphic analysis by our collaborators, Lincoln Conservation.

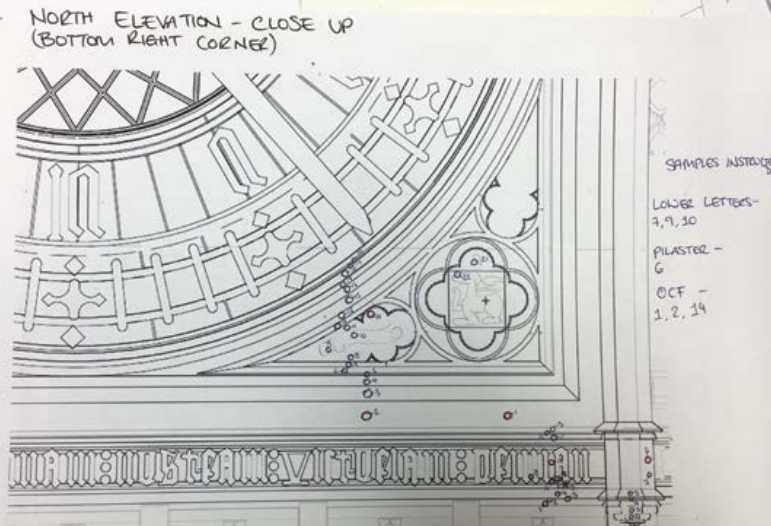

Detail of a marked up drawing for paint chip locations

We found that a mostly intact paint stratigraphy (the build-up of paint layers) existed in many of the areas we analysed. Before works, the inaccessibility of the exterior clock face surrounds had meant that no periodic cleaning or paint removal had ever taken place - each decorating campaign had been applied directly over the previous one, locking all preceding schemes away under a watertight barrier. This provided the sufficient evidence needed to remove all of the historical paint back to bare stone, revealing the blank surface needed to reinstate the original Charles Barry scheme.

Original Prussian Blue being uncovered on the East clock dial

What were the skills and techniques needed to unveil Elizabeth Tower’s decorative past?

Budget and programme are always the two main parameters to stick to and the skill of the conservation specialist is to only ever work within conservation ethics.

Paint stripping:

For the toughest and most labour intensive part, a combination of poultices, gentle steam and manual scrubbing was employed, adapted to the thickness of paint build-up, substrate texture, whether the surface was flat or carved, as well as the stubbornness of the hardened paint. The paint removal was carried out by hand to ensure no damage to, roughing up or muting of the fine quatrefoil carvings, which would not only accelerate the weathering of the stone but would make the gold leaf appear slightly dull as its shine is broken up across the uneven surface.

Painting:

The newly exposed underlying stone was in perfect condition and slightly less porous than the exposed stone, as deeply embedded microscopic alkyd-based paint particles were acting as a filler and slight water repellent. We needed to devise a paint system that would stay thoroughly adhered, even if moisture migrated behind it at its edges. So we used a base of silica masonry paint under all areas of decoration, including the gilding. Acting as a consolidant, it bonded to the silica in the stone and also helped to further smooth the substrate ready for the final finishing coats.

Once all paint had been removed - the stone in its clean virgin state

Gilding:

It was particularly challenging not only to gild at height on an exposed tower in all weathers but also to ensure that it stays fixed in place for many decades. Previous gilding was applied over a thick stable base of smoothed, hardened, impermeable alkyd paint, with little to no risk of moisture or salts migrating behind and delaminating the base coats.

Before gilding showing the paint build-up

Silica masonry paint will act in much the same way as the original paint did - creating a stable barrier and lifting the gold leaf away from the stone. Silica paint is permeable so to seal it we applied two coats of water-based primer and two top coats of oil-based gloss paint. We applied twelve hour gold size and gilded using a combination of 23.5ct loose and transfer leaf.

The Welsh Dragon completed

Can you tell us about the thinking behind reinstating the original decorative scheme?

The decorative scheme of the clockface surrounds is the only original external decoration that has not been retained or replaced like-for-like. Decorative schemes are often the feature that has undergone the most interference historically, each generation taking advantage of how relatively easy it is to paint over existing paint rather than re-carve stone or recast metal.

But this ease of application is only after the great difficulty of gaining access; in truth the decorative scheme is interfered with so frequently on buildings and monuments because it is vastly important and dictates the narrative of the people it represents.

In the case of Elizabeth Tower, the decorative schemes get more and more bold and severe as subsequent schemes are painted over until we end up with just black and gold over the whole clockface surround – as though each generation was attempting to blot out the previous one.

The reinstatement of the original Charles Barry scheme and all of the hard labour involved was - and always will be - worth it: the stripping away of all of the historical ‘noise’ has allowed the original architect to represent his building to us how he intended. Decorative schemes have no physical use other than to show the audience the personality of the creator, the human story behind the building.

Scaffold adaptions in late 2019 allowed for a fleeting view of the newly restored North clock face against the yet to be restored East clock face

Working at height and in extreme conditions must have been physically demanding, but were there also conservation challenges which needed to be overcome?

The team was strategically spread across the clockface’s many levels to stop overcrowding, however, the level of clean was different for everyone dependent on height and physical strength. To mitigate any patchiness the team was rotated regularly to ensure uniformity.

Work was year-round; the project kicked off in January 2018 during ‘The Beast from the East’ where temperatures up on the scaffolding plummeted to -8°C. In the heatwave of the following year, temperatures reached 45°C. During extreme weather, including strong winds or thunder and lightning, a judgement call was made on whether it was (first of all) safe and (secondly) if it was even possible to work. (Gilding, in particular, is more sensitive to wind and extreme weather than maybe painting or stone cleaning).

We were all aware that significant decisions made during the works would be heavily scrutinised, therefore a robust and concise argument was always put forward to the clients and stakeholders, and decisions were made jointly. An example of this is the St George’s Crosses that were reinstated on the stone shields above all four clockfaces at Belfry level. There was no material evidence gleaned from the analysis so the client relied on the Charles Barry 1838 watercolour, detailing his desired scheme which clearly includes St George’s Crosses above the clockfaces.

The narrow gangway up at Belfry Balcony level was barely 60 cm wide

What are your thoughts now the exterior works are complete?

Aesthetic desires need to be in line with the physical requirements for the longevity of the workmanship, especially on a surface totally inaccessible once the scaffolding is struck.

The scheme shows the hopeful outlook of the UK – as always, the face of Elizabeth Tower has been decorated to symbolise a national attitude. To me this most recent incarnation is we craftspeople flexing our muscles and pushing our expertise to the very limits. The results we have today would not have been possible during any other restoration campaign.

The robust documentation along with the sensitive yet thorough stripping away of the paint and the availability of state-of-the-art coatings ensures not only the health of the stone, but the stability of the decorative finishes, and of course it showcases the whole range of skills and expertise we have here at Cliveden Conservation.

The Elizabeth tower scaffolding and the completed works

What does working on this project mean to you?

This project has had a profound effect on me personally - especially as a born and bred Londoner. I will never forget it.

But there is another more valuable takeaway from this project - the diversity of the site team was exceptional. Conservation and restoration are already industries with strong diversity but this is made noticeable if we are involved in larger construction projects with trades which are traditionally male. Construction is particularly susceptible to this, and it is possibly why there are so few female operatives across most trades. On this project, there was a female scaffolder and a female stone mason. This project was to all intents and purposes a construction and engineering project. The presence of women on the team represents a more diverse future for these male-dominated industries.

This project is testimony to the skill available in the UK from operatives hailing from across the globe. It is often lamented that there is a conflict of interest when construction and heritage conservation are thrown together on a project, but this proves it not only works but is essential going forward - especially as more construction companies are venturing into heritage work. Working alongside heritage professionals and understanding the care and attention that must be afforded to these special buildings is the only way to ensure the future of our precious built heritage.

Elizabeth Tower: works completed